2026 calendarGardens in Kyoto

SCROLL

The city of Kyoto is surrounded on three sides by gentle mountain ranges, and there are independent hills scattered around the basin’s periphery, while the central area of the basin is dotted with ponds and pristine springs, and there are rivers and streams flowing from north to south. It is said that Emperor Kammu, who had relocated his seat of government from Nara to Nagaoka in 784 A.D. but was yet in search of another location for it, went on a scouting excursion and, coming to a spot that overlooked the Kyoto basin, was impressed by the beautiful scene that met his eyes, and recognized that this basin possessed all the geomantic properties required for a blessed, safe and prosperous capital. Hence it was, that a mere ten years after his move to Nagaoka, the Kyoto basin became the site for his new capital, known as Heian-kyō, or literally“ The Peaceful Capital.” And, insofar as our calendar theme is concerned, the natural environment and unique climate conditions inherent here have made Kyoto the perfect setting for the construction of gardens.

Although there is no single authoritative count as to how many so-called nihon teien, or“ Japanese gardens,” there are in Kyoto, no doubt there are hundreds. Indeed, superb Japanese gardens of every type, and representing every period in Japan ’s history, are to be found in this city. Needless to say, reflected in the various garden types are the cultural and religious characteristics of the historical age in which they evolved. To address this point, it is edifying to note that the primeval root of Japan’s gardens stems from this country’s indigenous Shinto religion, with its reverence for great rocks, lakes, ancient trees, and other spiritually inspiring phenomena of nature. In the ancient days when the capital was in Nara, there was the widespread adoption of Chinese culture and Buddhism by the emperor and aristocrats. That Chinese influence appeared in the gardens they built at their palaces, which often featured Taoist and Buddhist elements and attempted to reproduce famous landscapes. Taoist legends spoke of the Eight Immortals who inhabited five mountainous islands situated atop an enormous sea turtle, the place called Mount Hōrai, Land of the Immortals. The Immortals were carried there on the back of a crane. Owing to these legends, Japanese gardens commonly feature a mountainous island representing Mount Hōrai, and rocks representing turtles and cranes.

Japanese gardens are generally classified into five main categories. One is the chisen teien or“ pond-and-spring garden,” which features a central pond surrounded by artificial hills that depict natural landscapes. The pond often features islands and bridges. Some pond-and-spring gardens are designed for boating enjoyment. In fact, the garden with the oldest history in Kyoto would be the Shinsen’en, or “Sacred Spring Garden,” which is all that now remains of Emperor Kammu’s original palace and pleasure garden, and which falls into this garden category. When it was originally constructed around 794 A.D., it covered about thirty-three acres, and was part of a walled Chinese-style pleasure garden. It was the playground of the Heian nobility, who held moon-viewing and boating parties on the pond.

During the relatively peaceful early Heian period, the aristocrats devoted much of their time to the arts, and began building pond-and-spring gardens at their elegant residences and country villas. Unfortunately, none of those survive today. At Daikakuji temple, however, there is the boating pond called Ōsawa Pond, dating from the early Heian period, when this site was the detached imperial villa of Emperor Saga, son of Emperor Kammu.

Entering the late Heian period, Pure Land Buddhism, which focuses on achieving rebirth in the Pure Land or Western Paradise of Amida Buddha, gained popularity, and that gave rise to gardens designed to resemble that Western Paradise. Such “paradise gardens,” which were designed for meditation and contemplation, were built by noblemen who wanted to assert their power and independence from the Imperial household, which was growing weaker. The main pond-garden area at Byōdoin temple in Uji, south of Kyoto city proper, is a splendid example. Byōdoin features one of Japan’s most iconic buildings, the Phoenix Hall (National Treasure). This striking Chinese-style hall houses a large gilded statue of Amida Buddha. Notably, it stands on a central island in the pond, in which there is a small island representing Mount Hōrai, connected to the Phoenix Hall by a bridge which symbolizes the way to paradise. The image is as if the Phoenix Hall is an elegant palace in the Buddhist Pure Land. The view of it from across the pond, with its figure clearly reflected on the mirror-like surface of the water, is truly out-of-this-world.

The decline of the Heian period saw the shift of power from the imperial court to the warrior-class elite. There occurred two civil wars (1156 and 1159), which destroyed most of Kyoto and its gardens. By 1185, Minamoto Yoritomo of the Genji clan, who had imperial orders to raise troops and destroy the Heike clan, established himself in Kamakura, marking the beginning of the Kamakura period (1185‒1333). This medieval era in Japan’s history saw the rise of a warrior culture distinct from the aristocratic culture of Kyoto. In particular, the military rulers embraced the newly introduced Zen Buddhism, and this exerted a strong influence on their lifestyles and cultural values. Gardens became smaller, simpler, and more minimalist, matching the typically smaller-sized buildings of their residential compounds.

Amid this, the most extreme development towards minimalism was the karesansui teien or “dry landscape garden,” the second of the five main categories of Japanese garden. Gardens of this type employ only sand and stones to express the scenery of mountains and water, and are typically quite small. They are mostly found at Zen temples, where they are meant to help monks in meditation and religious advancement. The sand area is carefully raked into the proper design, a task requiring great mindfulness and generally carried out daily by one of the resident monks. This task in itself constitutes a form of Zen training. One of the best-known of all Japanese gardens is the dry landscape“ rock garden” at Ryōanji temple in Kyoto. The entire grounds of this Rinzai sect Zen temple originally stood as the villa of a Heian-period aristocrat. It was converted into a Zen temple in the mid-15th century. The date of construction of this temple’s famous rock garden, however, is uncertain, as is the identity of the garden’s designer. The garden is just 10 meters wide and 25 meters long, and features fifteen variously shaped and strategically positioned rocks that appear like small islands in a sea of white sand. The low clay wall that frames it on two of its far sides is extremely wabi-sabi in coloration, and is roofed so that a long eave hangs forward. Hardly detectable is that the clay wall tapers as it reaches the far corner, which gives the garden the visual illusion of being expansive. Beyond the wall, dense trees and bushes form the backdrop.

During the Kamakura period, the imperial court actually retained considerable power, and was able to exercise control over the areas around Kyoto. Powerful Buddhist temples, retired emperors, and court nobles also continued to wield considerable wealth and influence. In this scheme of things, the armed forces of Emperor Go-Daigo, led by the warrior Ashikaga Takauji, rose up against the government in Kamakura, and alas, the Kamakura period came to an end in 1333, and Imperial rule was restored. This, however, was short-lived, for Takauji betrayed the emperor, setting up his own military government headquarters in the Muromachi district of Kyoto, marking the beginning of the Muromachi (Ashikaga) period (1336‒1573). In this era, not only the Ashikaga, but their top vassals, and their retainers in turn, maintained homes in Kyoto. The third Ashikaga generalissimo, or shōgun, is known for having been a patron of the arts, and to have built the famous Kinkakuji, the Golden Pavilion temple, one of Kyoto’s most popular tourist attractions. The garden here falls under the third main category of Japanese garden, the kaiyū-shiki teien, or“ stroll garden.”

A Japanese stroll garden will have a well-designed path, or several interconnecting paths, which lead around it and offer lovely views along the way. Such gardens have their roots in the pond-and-spring pleasure gardens of the Nara and Heian period nobility, which centered around a large manmade pond. Rather than being for recreational enjoyments, however, they were more for quiet enjoyment.

While the “pond-and-spring garden” and “stroll garden” categories of Japanese garden inevitably are large gardens, there is, in contrast, the small tsuboniwa that became popular among the urban population, and which represents the fourth main category of Japanese garden. The word “tsubo” in the name for this type of garden refers to a traditional Japanese unit of area measurement equivalent to about 3.3 m2. Kyoto’s traditional machiya, or townhouses, which typically have a narrow frontage but extend quite far to the rear, are said to be the origin of this style. Tsuboniwa are built in confined courtyard spaces within or between townhouses, providing a touch of nature as well as light and fresh air. Fine old examples of these can be seen today at inns and restaurants.

Lastly, the fifth main garden category is that called roji, or literally“ dewy ground,” which is a special type of garden that emerged around the Azuchi-Momoyama period (1573‒1603), when matcha tea enjoyment saw its development into a comprehensive cultural pursuit unto its own. The roji serves as the approach to a tea room (chashitsu), a room designed for a host to receive guests for a gathering centering on the preparation and drinking of matcha tea. The guests make their way from the outside world to the tea room, gradually shedding their worldly concerns as they follow the pathway and purify their mouths and hands at the stone water-basin along the way. The water-basin is low and requires crouching down for use. Usually there is a stone lantern by it, for illumination during a tea gathering held after nightfall or before daybreak. Evergreens and moss are the only kinds of plants. Like the stroll garden, the path itself is carefully designed, and may feature various styles of paving.

Ah, the Japanese garden, which encapsulates scenes in nature and reflects Japanese aesthetic sensibilities. The Japanese garden, where we are invited into the boundary between nature and artifice.

Gretchen Mittwer

COVER : Tenryūji Temple Sōgen Pond Garden

Tenryūji is the head temple of the Tenryūji branch of the Rinzai school of Zen Buddhism. It was founded in 1339 by the first Ashikaga shōgun, Ashikaga Takauji, on the site of the former Kameyama palace of Emperor Go-Saga, to pray for the repose of the soul of Emperor Go-Daigo, who resided here. Within the temple grounds lies the Sōgen Pond Garden, laid out nearly seven hundred years ago by the Zen master Musō Soseki, the temple’s founding priest. It was the first place in the country to win designation by the Japanese Government as a Site of Special Historic and Scenic Importance. This stroll garden masterfully incorporates the Arashiyama hills on the far bank of the Ōi River and Mount Kameyama to the west as“borrowed scenery,”which effectively adds visual depth to the garden. Looking directly across the pond from the center of the large Hōjō building’s veranda, one can see the arrangement of rocks that represent Dragon Gate Falls, a waterfall on the Yellow River in China. Chinese legend has it that any carp able to scale this waterfall turns into a dragon, a transformation that in Zen has come to symbolize enlightenment.

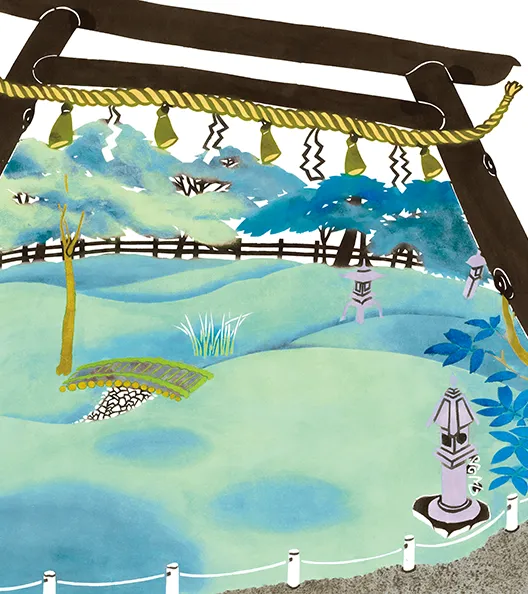

January - February : Kyoto Sentō Imperial Palace

The Kyoto Sentō Imperial Palace was built in 1630 as a palace for the retired Emperor Go-Mizunoo, who had abdicated the throne. The “Sentō” in its name means “hermit’s dwelling.” Today, only the tea house named Seikatei and stroll garden remain. This garden was created by the Tokugawa government official Kobori Enshū in 1636, and is said to have been modified by the retired Emperor Go-Mizunoo in 1664. It has a north pond and a south pond. The curving shore of the south pond is spread over with approximately 120,000 palm-sized round stones, exuding an air of refinement.

March - April : Jōjakkōji Temple Fresh Verdure

Jōjakkōji temple, located on the slopes of Mount Ogura in the Arashiyama area of Kyoto, is a lovely Nichiren sect temple not widely visited by tourists. Since the Heian period, court nobles and poets favored this scenic area, and many of them built their country villas and hermitages here. The area is known for its Japanese maples, and is one of Kyoto’s premier spots for viewing them. Passing through the Niōmon gate of Jōjakkōji in the early spring, when the maples put forth their fresh new leaves, the lush green moss and luminescent green of the maples is breathtaking.

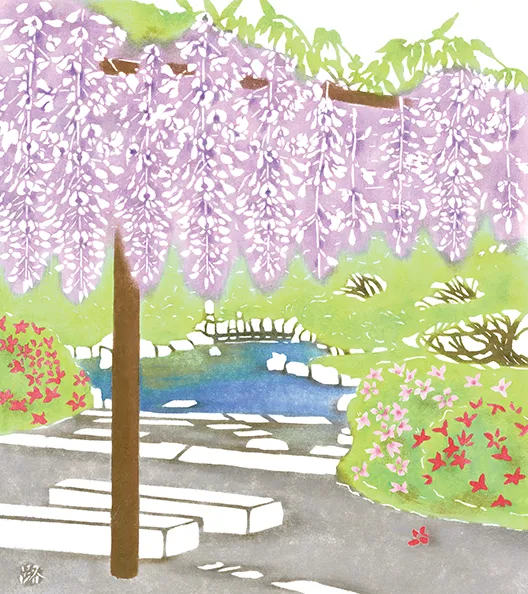

May - June : Jōnangū Shrine Rakusuien Garden

Jōnangū shrine, the shrine that protected the south of the capital, is located in a dense wooded area in Fushimi. When Emperor Shirakawa (1053–1129) built his Toba Villa (Jōnan Rikyū), the shrine became part of the estate. The relatively modern Rakusuien is a vast stroll garden that surrounds the shrine buildings and features a Spring Mountain, Heian Garden, Muromachi Garden, Momoyama Garden, and Jōnan Rikyū Garden. Plants that appear in the Tale of Genji have been planted here and there, and so the entire Rakusuien is known as “the flower garden of the Tale of Genji.”

July - August : Nonomiya Shrine Moss Garden

Nonomiya shrine is a small, secluded shrine located in Kyoto’s famous Sagano bamboo grove — an area in Kyoto which attracts many tourists. The shrine was originally built as a sacred house for the Saiō-to-be (unmarried princess chosen to serve as Saiō, or “Imperial Priestess,” of Ise Grand Shrine) to prepare herself through purification. Mention of it appears in the Tale of Genji, and so the shrine is popularly linked to that epic Heian-period novel. On its grounds, there is a beautiful moss garden, within which there is a small bridge crossing over white sand that represents a river.

September - October : Yoshiminedera Temple Japanese Anemones

Yoshiminedera is a Tendai sect temple located at Mount Shakadake in western Kyoto. Built along the mountain side, its grounds form a vast stroll garden with gorgeous scenery throughout the year. Its famous “Playing Dragon” pine tree, designated as a National Natural Monument, is over six hundred years old, and was trained to grow horizontally, so it stretches over a length of about 40 m. The temple’s two-story pagoda is a National Important Cultural Asset. In early autumn, some 5,000 Japanese anemones bloom throughout the temple grounds, and sway gently in the breeze.

November - December : Tōjiin Temple Fuyōike Pond

Tōjiin temple, lying at the foot of Mount Kinugasa in the northwest part of Kyoto, is known as the ancestral temple of the Ashikaga shōguns, and is a ‘hidden gem’ for its superb gardens. The gardens feature Shinjiike Pond, shaped like the kanji for “heart,” and Fuyōike Pond, designed to resemble a lotus flower. On a hill across from these is the Seirentei tea house. The gardens were designed by Zen master Musō Soseki, who the first Ashikaga shōgun, Takauji, had positioned as the founding priest of Tenryūji temple in 1339, and two years thereafter, as the first abbot of Tōjiin.