2025 calendarA Visit to The Tale of Genji Locations in Kyoto

SCROLL

Over a millenium ago, during the Heian Period (794‒1185) in Japan’s long history, a woman who we known of as Murasaki Shikibu (d. 1014) wrote an incredibly rich tale that is widely regarded as the greatest work of Japanese literature, The Tale of Genji, said to be the world’s oldest novel. Very little is actually known of this woman; her name as we know it derives from the heroine who makes her first appearance in the work’s Part Five, entitled “Young Murasaki,” and her real father’s position at the Bureau of Rites (Shikibu).

The eminent scholar of classical Japanese literature, Kikan Ikeda (1896‒1956), analyzed the tale as constituting three divisions,“ three phases of life̶glory and youth, conflict and death, and transcendence of death…. These three divisions are unified by a concern with human fate.” (The Princeton Companion to Classical Japanese Literature, p. 204) The passions and sensibilities of the characters, fictional figures belonging to a not so fictional aristocratic society highly defined by rank and status, are ingeniously expressed through the prose in which this fifty-four-part work is written, and the nearly eight hundred poems which are included.

The tale’s opening words, written in the now antiquated Japanese of those days, may be rendered into English like this: “In what emperor’s era was it, now, that among the many ladies of the court, there was one who, though not of extraordinarily high birth or rank, the emperor loved deeply.” The lady is Kiritsubo, so called because the apartment where she resides within the Kyoto Imperial Palace has the courtyard (tsubo) featuring a paulownia (kiri). Her name serves as the title of Part One,“ Kiritsubo.”

In this first part of the intricately woven story which is about to unfold, we are introduced to Kiritsubo’s circumstances and those of the emperor’s second son, the boy she gave birth to, our protagonist Genji. The emperor dotes on Kiritsubo and their beautiful boy, Genji, which spurs hateful harassment from the other ladies. Especially hateful is Kokiden, the high-ranking mother of the emperor’s first-born son, the ‘rightful’ future crown prince. Kiritsubo, plagued by people’s jealousy, tragically falls ill and dies when Genji is but the age of three. The emperor is plunged into mourning.

The young, motherless Genji eventually excels in both scholarship and music, and his father, the emperor, considers naming him crown prince. However, the emperor heeds the words of a physiognomist who predicts that it would lead to political strife, and demotes Genji from his position even as an imperial prince, making him a vassal of commoner status.

The emperor’s longing for Kiritsubo at last wanes once Fujitsubo, who bears a striking resemblance to her, enters his service. She is the fourth princess of a previous emperor, and is placed in the apartment with the wisteria (fuji) courtyard. The emperor comes to love her deeply, and Genji, for his part, develops a great fondness for her. Meanwhile, Genji’s coming-of-age ceremony takes place, and he marries Aoi, a daughter of the Minister of the Left. Aoi is a prideful woman and, being some years older than Genji, is cold and stand-offish toward him.

Gretchen Mittwer

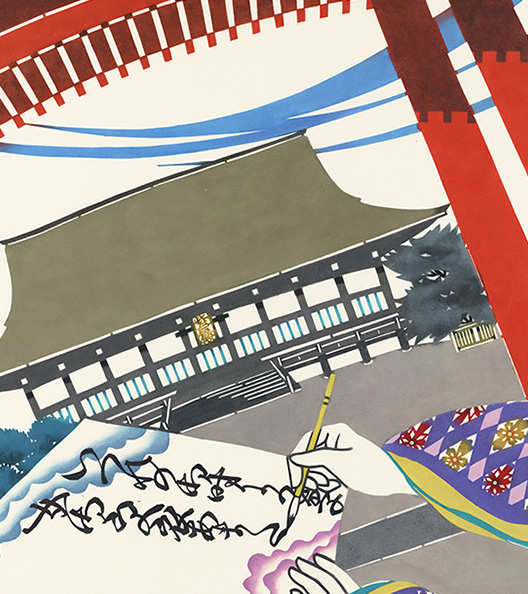

COVER : Kyoto Imperial Palace Shishinden

In that, overall, The Tale of Genji tells of the lives of the imperial family and nobility, many of its scenes take place right here within the Imperial Palace and particularly at the elegant Shishinden, the emperor’s residential facility. Part Eight, entitled“ The Cherry Blossom Party,” is a good example. Spring has come, and Genji is now twenty years old. The emperor and various members of his inner family circle are assembled at the Shishinden, for a party to admire the“ Cherry Tree of the Left” that was in beautiful bloom in front of this grand building. Genji receives a request from the Crown Prince to perform the noh chant and dance about the singing of the nightingale in spring. Genji, hardly in a position to decline, stands up and, in an apologetic manner, performs just a portion of it. However, even that much is so wonderful that it brings tears to the eyes of the Minister of the Left, who had been angry with him.

January - February : Kamigamo Shrine

The artwork, by the textile dyeing artist Michiko Kasugai, is of Kamigamo Shrine, in the northern area of Kyoto city. The “Carriage Skirmish” incident between Genji’s wife, Aoi-no-ue, and Lady Rokujō, is described in Part Nine of The Tale of Genji. It occurs on the day of the purification ceremony and carriage procession leading to it that, to the present day, is a highlight of the Kamo Festival (Aoi “Hollyhock” Festival). Following the fateful incident, Aoi-no-ue gives birth to Yūgiri, but then suddenly dies. After the mourning period, Genji formally ties the knot with Murasaki.

March - April : Ninnaji Temple

The artwork, by the textile dyeing artist Michiko Kasugai, is of Ninnaji, the head temple of the Omuro branch of Shingon Buddhism. The name of the area where it is located, Omuro, has the meaning that it is where nobles enter the priesthood and reside. Construction of Ninnaji began in 886, as an imperial temple for Emperor Koko. His successor, Emperor Uda, moved in as its first head priest, and it became called the Omuro Imperial Palace. In part Thirty-four of The Tale of Genji, the Retired Emperor Suzaku leaves the secular world and moves to such a temple in the hills.

May - June : Sanzen’in Temple (Ōjō Gokurakuin)

The artwork, by the textile dyeing artist Keijin Ihaya, is of the Amida triad enshrined in the Ōjō Gokurakuin (Amida Hall; first built in 985) at the imperial temple named Sanzen’in, in the district of Ohara deep to the northeast of the Kyoto basin. Part Thirty-nine of The Tale of Genji, entitled “Yūgiri” (“Evening Mist”), focuses on Princess Ochiba, who has moved with her ailing mother to “the mountain villa at Ono” so as her mother can receive the ministrations of a holy man from Mount Hiei. It is theorized that this mountain villa at Ono refers to Sanzen’in.

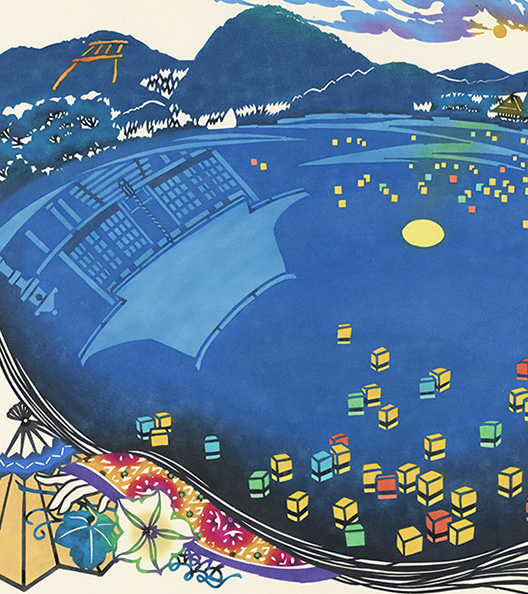

July - August : Hirosawa Pond and Henjōji Temple

The artwork, by the textile dying artist Keiko Kanesaki, shows Hirosawa Pond on the night of the lantern floating for Obon. Ever since the Heian Period, this large pond that is part and parcel of Henjōji Temple has been a famous moon-viewing spot. The pond and temple do not appear in The Tale of Genji, but the inspiration for the Part Four story about Yūgao supposedly was a shocking incident the author found out about in real life. Imperial Prince Tomohira had secretly taken his concubine moon-viewing at Henjōji, where an evil spirit possessed her and she died.

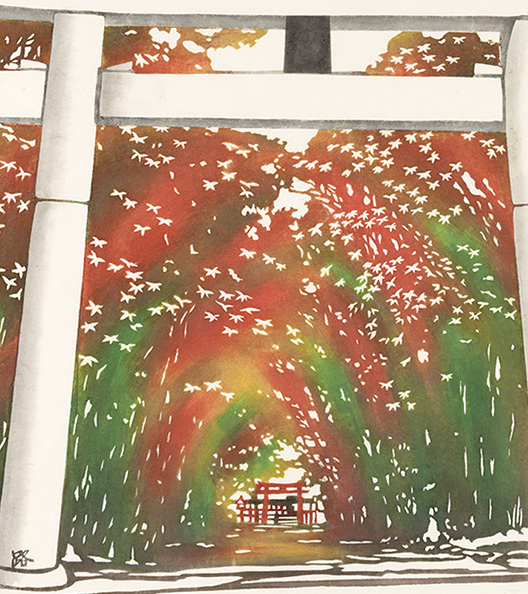

September - October : Nashinoki Shrine

The artwork, by the textile dyeing artist Keijin Ihaya, is of Nashinoki Shrine when its famous bush clovers are in bloom. Although this shrine was built less than a century and a half ago, it lies on property formerly occupied by the aristocratic Sanjō family, whose founder was of the Fujiwara clan. This Sanjō family branch of the Fujiwara clan arose in the Heian Period, and its name derives from the location of the family’s estate, along Sanjō Avenue. Part Twenty-eight of The Tale of Genji makes mention of Yūgiri going to look in on his grandmother, Princess Ōmiya, at Sanjō.

November - December : Ōharano Shrine

The artwork, by the textile dyeing artist Michiko Kasugai, is of the elite Fujiwara clan’s ancestral shrine at Ōharano. The shrine, a branch of Kasuga Taisha Shrine in Nara, was founded during the decade (784–794) when Nagaoka was the capital, preceding the transfer of the capital to Kyoto and beginning of the Heian Period. Throughout its early history, members of the imperial family, including the Fujiwara with whom they were inseparably intertwined, often visited this shrine and enjoyed hunting in the Ōharano countryside. Part Twenty-nine of The Tale of Genji, entitled “The Imperial Visit,” has Emperor Reizei making such a visit.