2022 calendarOld Sayings about Kyoto

SCROLL

It would take many tomes to relate the history and traditions that make up the fabric of Kyoto, this city which was the capital of Japan for over a millennium. In this year’s calendar, we take up a few old sayings related to certain famous historical events, places, and customs. Through them, we are able to draw out some of the finer threads which lie interwoven in that fabric, and fill in a bit more of the intricate tapestry that represents the city of Kyoto in all its dimensions and shades of color.

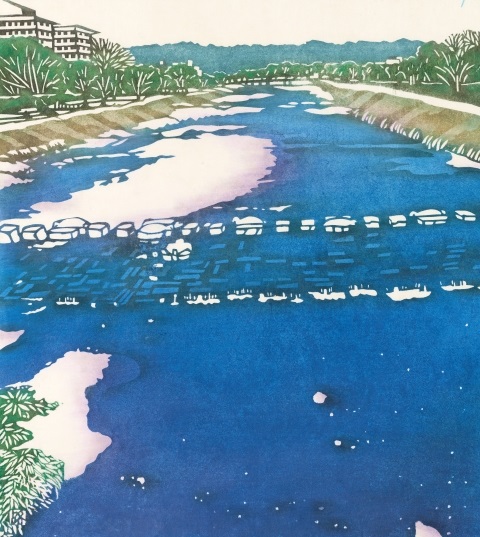

The artwork on the January-February page shows the Kamogawa River which flows from north to south down the eastern side of the city, and which is among this city’s most familiar scenic features. In the context of this year’s calendar theme, it leads us to the old saying that “Heian-kyō, the Capital of Peace, is a city that matches with ‘the four godly spirits’.”

Heian-kyō, or “Capital of Peace,” was the name given to Kyoto when this city was originally constructed and established as the seat of the emperor and his government in 794 A.D., following its move from Nara and its short period of residence in Nagaoka-kyō, located west of Kyoto. The reigning emperor at the time was Kanmu (737-806), whose remarkable accomplishments ― especially, his establishment of the “Capital of Peace” ― place him among the most famous emperors in Japanese history. When he was searching for an appropriate site to build his new, magnificent capital that would be a fortress-like haven from the forces attempting to invade and overrun it ― forces which had caused him to abandon Nara in the first place ― his concern was to find a site that met four topographical conditions. Those conditions had their basis in Chinese theories of geomancy, and were related to the Chinese concept of “the four godly spirits” which reign over the four cardinal directions of the constellations.

“The four godly spirits” take the imaginative form of four fantastic creatures. Governing the north is Genbu, a tortoise encircled by a serpent; governing the east is Seiryū, an East Asian form of dragon; governing the south is Suzaku, a giant vermilion bird resembling a phoenix; and governing the west is Byakko, a white tiger. Emperor Kanmu, when he came upon the Kyoto basin, had found the perfect site. It had the necessary mountain in the north, river in the east, lake in the south, and roadway in the west. Specifically, there was Mount Funaoka in the north, the Kamogawa River in the east, the large Oguraike Pond (no longer extant) in the south, and the San’indo Road along the west. Emperor Kanmu had his new capital built on the model of China’s cosmopolitan capital of the Tang Dynasty, Chang’an. It was laid out in a grid pattern, with a wide central avenue which dissected the eastern and western quarters. Here, in and around the Capital of Peace, there flowered the elegant culture of Japan’s Heian Period (794–1185).

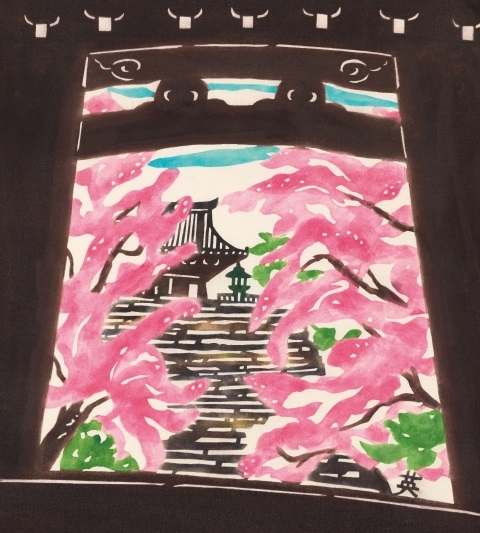

Moving to the March-April page, the artwork offers a view through the massive front gate of Konkai Kōmyōji temple on a spring day when the cherry blossoms are at their peak. This serene temple, also known as Kurodani, traces its founding to the year 1175, when the founder of Japan’s Pure Land (Jōdo) sect of Buddhism, St. Hōnen, stayed at this location after leaving the monastery at Mount Hiei in the northeast of Kyoto, and came down into the city to propagate his new Pure Land teaching. Among the impressive structures on the temple grounds, there is a three-storied pagoda which enshrines a statue of the legendary bodhisattva Manjusri (Monju bosatsu). Manjusri was endowed with great wisdom and thus has been revered as a symbol of wisdom. The Japanese have an old saying, “If three people get together, the wisdom of Manjushri,” which is to say that the combined wisdom of three people can produce astoundingly wise results. With its reference to Manjushri, this familiar old saying, often likened to the English proverb that “two heads are better than one,” is revealing of the pervasive influence of Buddhism in Japan.

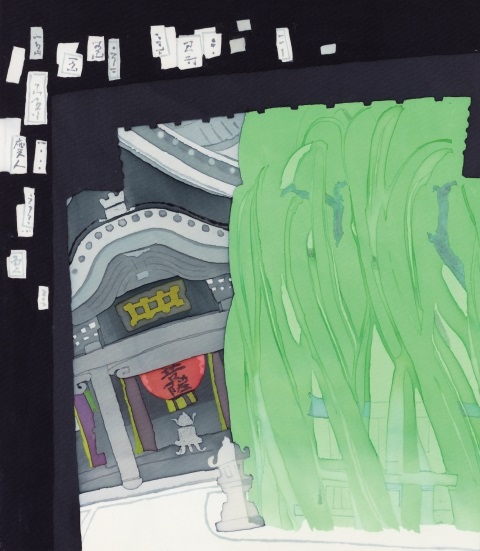

The artwork on the May-June page shows the entrance gate of Chohōji temple, familiarly known as the Rokkakudō or “Hexagonal Temple,” located near the center of downtown Kyoto. It is summer, and the willow tree that stands just within the old gate is lush. Venture through gate, and one can see the hexagonal main temple pavilion with its unique slate tile roof, as well as other six-sided things here and there. Among them is a relatively flat stone just 45 cm in diameter, having a hole in the center. It is said to represent the navel of Kyoto.

The history of the Rokkakudō supposedly predates the founding of Emperor Kanmu’s Capital of Peace. According to legend, it was founded by Prince Shōtoku (574–622), who was camped at the site after having gone swimming in the pond there on that hot summer day. In the night, he had a dream in which the bodhisattva Kannon, “Goddess of Compassion,” appeared before him and told him to build a six-sided temple on the spot and enshrine her within it. Going by this, the Rokkakudō was in existence almost two centuries before Emperor Kanmu drew up his city plans. The plans had it that a street would cut through the Rokkakudō. Something had to be done to save it, so the Emperor sent a messenger to make prayers and plead, “Please move a little.” And what do you know, the six-sided pavilion enshrining the bodhisattva Kannon moved to its current location about 15 meters north overnight. However, one cornerstone was left behind; the so-called navel stone, or “hesoishi,” that has come down to the present day. For centuries, it was situated in the middle of Rokkaku-dōri street, and closely marked the center of the city, but because of traffic concerns, it was relocated to its present site at the temple. It may not exactly mark the center of Kyoto, but still is known as “the navel stone of the Rokkakudō,” or also, “the navel stone of Kyoto.”

For July-August, we see a feast of gourmet delights such as one might enjoy in Kyoto around the time of the famous Gion Festival that takes place over the month of July. The festival is represented in the picture by a red, miniature festival float rooftop halberd decorating the table, and the paper lanterns which are hung as offerings of light to the Shintō deities to which the festival is dedicated. All the various foods have hamo, the Japanese word for pike conger, as their chief ingredient. This is all to represent the old saying that “the Gion Festival is the hamo festival.”

In ancient times, hamo was one of the few fish tough enough to survive a multi-day journey to the inland capital. It is an aggressive fish with sharp teeth and long, eel-like body, and it has an astonishing 1,200 bones which are impossible to remove. It was prized by the Kyoto aristocracy, and it remains an expensive Kyoto delicacy. Especially at the end of the rainy season, this white-meat fish is rich in umami and nutrition, and that is when it is considered hamo season in Kyoto, where chefs are highly trained in the art of making the bones virtually disappear. This involves using a very sharp, large and heavy knife to make precision cuts in the fish’s opened body without cutting the skin, at about 24 cuts per inch, or 8 cuts per cm. This renders the bones unnoticeable and edible. The Kyoto aristocracy, with their delicate cultural tastes and sensibilities, were directly or indirectly responsible for the development of many of the fields of craftsmanship for which Kyoto has been known, and we could say that the art of preparing hamo is among them.

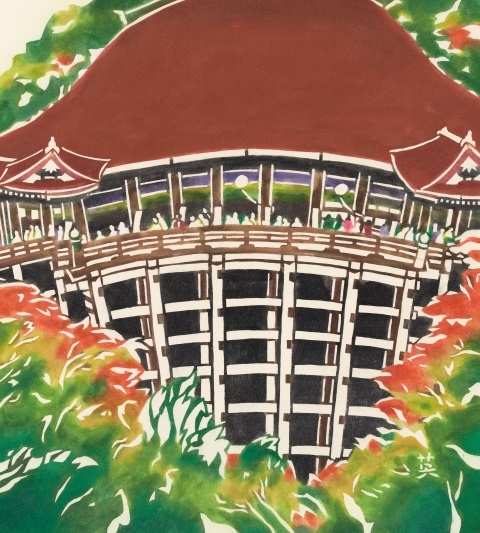

On the September-October page is a view of the magnificent main building of one of Kyoto’s most famous temples, Kiyomizu-dera, the “Temple of Pure Water,” located halfway up Mount Otowa, one of the peaks in the mountain range along the eastern side of the Kyoto basin. Kiyomizu-dera actually comprises thirty Buddhist buildings, spread over thousands of square meters along the slope of Mount Otowa. Its National Treasure main building is the one famed for its wide balcony overhanging the steep slope below, supported on wooden pillars and crosspieces which act as scaffolding and have sturdily upheld the building through centuries of earthquakes and heavy storms. This balcony offers a picturesque view of the city nestled in the basin beyond, with gorgeous scenery that spreads out in the foreground below. The wide balcony, referred to in Japanese as the temple’s butai, or “stage,” is the place given in the old phrase, “To jump off the Kiyomizu stage,” used to mean “take the plunge and hope for the best.”

The year’s last page, for November-December, has to do with the saying that “if the Kōbō-san day is fair weather, the Tenjin-san day will be rainy.” The artwork shows a scene around one of the entrance gates of Tōji Temple on one of its “Kōbō-san” festival days held on the 21st of each month, which attracts throngs of pilgrims and others out to enjoy the flea market for which the festival is well-known. Just five days from this monthly festival at Tōji Temple, there is the equally popular monthly Tenjin-san festival held on the 25th at Kitano Tenmangu Shrine, with its flea market.

The weather around Kyoto, even in these unpredictable times, tends to change in a relatively regular cycle, so that oftentimes if skies are clear on one day, rain clouds will dominate around five days later. People with interests in the Kōbō-san and Tenjin-san festivals, including the flea-market vendors themselves, are keen to have the festival fall on a clear, dry day, for the weather greatly affects the number of visitors, and the vendors might not be able to even set out their goods. It will be especially wonderful if both festivals this year, 2022, can be held amid fine weather, removed from pestilence and the ravages of any natural disasters.

Gretchen Mittwer

Cover:The Honnōji Incident

Decorating the calendar cover is a fiery scene of Honnōji Temple going up in flames. It is the early morning of the 2nd day of the 6th month in the year 1582 The clever and ruthless hegemon, Oda Nobunaga, caught off-guard at this temple in Kyoto ― a temple which he had been instrumental in rebuilding a few years earlier ― has been attacked by his trusted vassal, Akechi Mitsuhide. Hopelessly outnumbered, Nobunaga realizes his defeat and chooses to set his room on fire and commit seppuku. It was indeed a surprise attack. Nobunaga, while he himself was working on subtle strategies at his base, Honnōji, in the capital, had sent his captains out to subjugate the regional forces opposing his leadership. Akechi Mitsuhide, with an army of 13,000, was ordered to go and help with the takeover of Takamatsu Castle, but he turned his troops around, uttering his famous words, “The enemy is at Honnōji!” Those words are the origin of the common Japanese phrase, “tekihon-shugi,” meaning “diversionary tactic.” The reason for Mitsuhide’s betrayal remains a matter of conjecture. It is one of the great mysteries in Japanese history, and has been the theme of novels, movies, and TV dramas.

January - February:The Kamogawa River

The artwork on this page, by the Kyoto-based textile dyeing artist Michiko Kasugai, shows a scene of Kyoto’s Kamogawa River. Around the year 794 A.D., when Emperor Kanmu was searching for a site to build his new capital that would be a fortress-like haven from the forces attempting to invade it, he had to find a site that met four conditions related to the Chinese concept of the “four godly spirits” which govern the four cardinal directions. The Kyoto basin, with its northern mountain, eastern Kamogawa River, southern lake, and western road was the perfect site.

March - April:Konkai Kōmyōji Temple

The artwork on this page, by the Kyoto-based textile dyeing artist Hideharu Naito, offers a glimpse through the huge entrance gate of Konkai Kōmyōji Temple. It is spring, and the cherry blossoms are gorgeous. The temple buildings on the grounds include a three-story pagoda enshrining a statue of the bodhisattva Manjusri, or Monju bosatsu. Manjusri is revered as a symbol of wisdom, and the Japanese have an old saying, “If three people get together, the wisdom of Manjushri,” meaning that the combined wisdom of three people can produce astoundingly wise results.

May - June:Rokkakudō Temple

The artwork on this page, by the Kyoto-based textile dyeing artist Keijin Ihaya, shows the entrance gate of Rokkakudō, the “Hexagonal Temple,” located just a short stroll from the intersection of Karasuma and Oike streets, near the center of downtown Kyoto. It is summer, and the willow trees on the grounds are lush. Venture through the gate, and one can see the temple pavilion with its unique hexagonal roof, as well as other six-sided things here and there. Among them is an unassuming stone having a hole in the center, said to represent the navel of Kyoto.

July - August:The Gion Festival

The artwork on this page, by the Kyoto-based textile dyeing artist Keiko Kanesaki, whose work was also on the cover, shows an array of gourmet delights featuring the pike conger as their chief ingredient. The lanterns and other decorations indicate that it is the time of Kyoto’s mid-summer Gion Festival, held all through July. Pike conger is most delicious this time of year, but due to its hundreds of unremovable bones, special skills are required to make it edible. From olden times, chefs in Kyoto have been trained in the difficult art of preparing this fish.

September - October:Kiyomizu-dera Temple

The artwork on this page, showing the magnificent hondō or “main hall” of Kiyomizu-dera Temple, is by Hideharu Naito, whose work also decorated the March-April page. Kiyomizu-dera covers a vast area on the slope of Mount Otowa, and its hondō, a National Treasure, juts out over the valley, supported on pillars and crossbeams. Through the ages, there have been many cases of desperate people jumping off of the balcony, but usually surviving the plunge. “To jump off the Kiyomizu stage” is an old phrase which is used to mean “take the plunge and hope for the best.”

November - December:Tōji Temple

The artwork here is by Michiko Kasugai, whose work also decorated the January-February page. We see a scene at Tōji Temple on a monthly Kōbō-san day, the 21st of the month, when there are many vendors in and around the precincts, catering to the visitors who throng here on this day. On the 25th, Kitano Tenmangu Shrine has its monthly Tenjin-san festival, with its equally popular ‘flea market.’ Since the weather looks fine in this Kōbō-san festival day scene, the Tenjin-san festival five days away may meet with rain, according to Kyoto’s usual weather cycle.