2020 calendarkyoto and Rakugo Japan's Traditional Art of Humorous Story-telling

SCROLL

Among the genres of Japan’s traditional performance arts, there is Rakugo, a popular form of comic monologue in which a storyteller, seated in the formal seiza style on a cushion in the middle of the stage which is devoid of any scenic props, performs an imaginary drama through episodic narration and skillful use of vocal and facial expressions to portray various characters. The term “Rakugo” translates literally as “drop word,” and this name for the genre was coined from the fact that the storyteller’s delivery characteristically ends with a punning punch line, “the drop.”

In that Rakugo is a traditional entertainment, it adheres to certain traditions which typify it. The stage setting, with simply the sitting cushion for the storyteller, is one of these. Being devoid of scenic props, it gives freedom to the audience’s imagination, something like if they were listening to an enrapturing storyteller on the radio. Much of the joy of Rakugo, however, lies in watching the storyteller’s every move as he brings the story to life. He wears a plain kimono and kimono jacket. He carries a folding fan, a traditional must-have for proper etiquette. When he comes onto the stage, he places his folding fan before him and bows low before taking his seat on the cushion. With originality which will draw his audience in, he leads into the familiar story which he is about to tell, and eventually his folding fan becomes an almost magical tool for him in enacting the imaginary drama, turning into such varied things as perhaps a saké flask, a walking stick, or a police magistrate’s stick. Usually, his only other concrete tool is the hand towel he carries in his kimono pocket.

The stories in classic Rakugo date mainly to the Edo or Meiji periods, or around the 17th to 19th centuries, and are time and place specific, requiring that the audience have knowledge of the particularities of those circumstances in order to fully appreciate the performance. The insight that can be gained about these things of olden Japan is a part of the Rakugo aficionado’s enjoyment. In that the stories poke fun at human foibles and basic human nature, however, audiences never tire of them. The refreshing manner in which the expert storyteller is able to characterize the plot is always new and entertaining, and so classic Rakugo enjoys popularity to this day.

Among the rather small repertory of classic Rakugo, there are stories related to places in Kyoto. In this year’s calendar, those places are introduced by introducing the stories with which they are connected. So, on the January-February page, we begin with the story, “The ‘Humm?’ Tea Bowl,” which takes us to the Otowa-no-taki Waterfall at Kiyomizudera Temple. The story opens with Kyoto’s top appraiser of tea implements, who has the nickname “Tea Gold,” drinking tea at a refreshment shop by the waterfall. Finishing the tea, he examines the bowl it was served in with great thoroughness, tilts his head, and murmurs “Humm.” Observing this is “Oil Vendor.” After Tea Gold leaves, Oil Vendor buys the tea bowl from the shop for two gold coins, all the money that he has. He takes it to Tea Gold’s store and offers to sell it for a thousand gold coins, but Tea Gold tells him that, though the bowl has no flaws, it leaks and is hardly worth anything. The ensuing twists in the plot tell how Tea Gold takes pity on Oil Vendor, and manages to get some elite prestige added to the bowl. The Emperor’s Councilor composes a poem for it which alludes to the Otowa-no-taki, and the bowl’s box receives the imperial inscription, “Humm.” The bowl thus finds a buyer for a thousand gold coins.

For the March-April page, we are at Mount Atago, where a gentleman of the sort called a danna ― a man of means who typically enjoys such amusements as partying with maiko and geisha ― brings a small group of playful maiko and geisha on a hiking excursion. It is an arduous climb up the mountain, and the main character in this story, a male geisha named Ippachi, goes through various comical trials in keeping up with the energetic others. At the resting point halfway up the mountain, there is a shop that sells small bisque ware saucers for hikers to toss into the deep valley below, for fun. The danna is adept at this, but Ippachi, to his own chagrin, fails sadly. Ippachi’s excuse is that where he is from, Osaka, people toss coins, not saucers. Surprisingly, the danna has 20 rare gold coins readied for just this, and tosses them into the valley. Whoever eventually finds them can have them, he says. Ippachi, eager to have them, borrows a large umbrella from the shop, thinking he can use it to parachute down. After getting a push from behind, he lands amid the patch of gold coins. He calls out his success in finding all 20 coins. The danna calls out, “Good! And now, what’s your plan for getting back up here?” Ippachi thinks, “Yikes!” He is quick-witted, however. Ingeniously, he tears up his silk undergarment to make a long rope, ties a rock to one end and flings it up so the rope latches onto a bamboo growing on the mountainside, pulls the bamboo into a taut bow, lets it loose, and lands back with the others in one amazing swoop. The danna is impressed, and enquires about the gold coins. “The gold coins? Yikes, I forgot them down there!” So ends this comical tale.

The May-June site is the ancient imperial garden called Shinsen’en, and the story title might be rendered as “Wordplay Komachi,” Komachi being the famous ancient poetess, Ono-no-Komachi. This relatively modern story takes place wholly in Osaka, and has Kanbei calling on Sasuke. Sasuke’s disgruntled “ol’ lady” is a woman packed with silly yet amazing verbal dexterity and little sophistication. She tells Kanbei that her good-for-nothing husband is out and has secretly been patronizing a young woman belonging to a tea house in the pleasure quarter. She describes how she tailed him there, barged into the tea house, dragged him home, and gave him an earful. Kanbei offers her suggestions as to how to win Sasuke’s devotion. She should treat him tenderheartedly, and develop tact and finesse in her way of communication. Kanbei brings up the example of Ono-no-Komachi’s effective rain prayer poem composed at Shinsen’en, a poem containing eloquent plays on words. Sasuke’s ol’ lady promptly dives into a nonsensical tirade using all manner of wordplay.

For July-August, the story is “Ghost Candy.” It is the year 1599, and the site is Rokudo Chinnoji Temple, believed to stand at the border between this world and the afterworld. One night, a pale woman appears at the candy store in front of the temple, to buy a piece of candy with the one-mon coin she has. This happens for six nights straight. On the seventh night, she is without money. The storekeeper gives her the usual piece of candy, and decides to follow her. She enters the graveyard at Kodaiji Temple and disappears. From a grave, however, a baby can be heard crying, so the storekeeper excavates the grave and is able to save the baby. The woman had been pregnant when she died, and had somehow given birth after she had been laid to rest. Six one-mon coins had been placed in her coffin, as fare for the boat which would take her across the river to the afterworld. She had used them for the candy she bought to feed her baby. It was a little boy, who grew up to become a priest at Kodaiji. “Ko o daiji.” (This short last phrase, nearly a homophone for the temple name, means “to lovingly caring after one’s child.”)

The September-October story, “Hip-pouch Kosuke” (alternately, “Commotion Kosuke”), is about Kosuke, a super-earnest bloke who has made a life for himself in Osaka as a log splitter and enjoys his reputation as a quarrel mediator. He hasn’t a clue about popular amusements. His single joy lies in stepping in when people are quarreling, and pacifying them. He is known to often go all-out in treating quarrelers to food and drink, over which they can mend their differences. A couple of chaps know this, and rig a fight together, aiming for Kosuke to step in. This somehow works out for them. Kosuke, always on the prowl for a quarrel, hears the shouts and pleas of two women. Eager to intercede, he innocently comes into a lesson room where amateurs are practicing the art of dramatic storytelling. The dramatic recitation he overheard was a short bit from a popular story in which, at an old obi shop near the corner of Yanaginobanba and Oshikoji in Kyoto, the wife of the proprietor suffers outright bullying by her oppressive mother-in-law. The lesson room mistress explains about the place and characters involved in the story, but Kosuke can’t get it through his thick skull that the characters and squabble are make-believe. He jumps onto the overnight boat to Kyoto and finds his way to Yanaginobanba Oshikoji. There just so happens to be an obi shop right there. Although Kanbei’s explanation of who he needs to see makes no sense to the shop manager, Kanbei learns that the two women who possibly match the description are dead. He jumps to the conclusion that, regretfully, he was a day late in stopping them from killing each other.

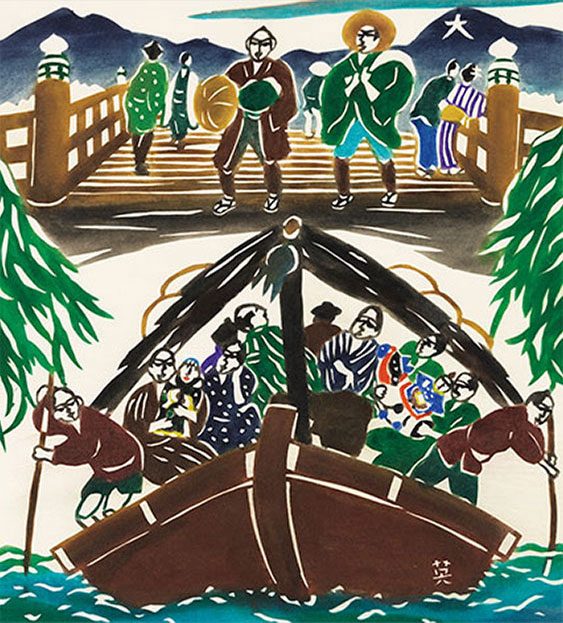

The inspiration for the November-December page is the classical Rakugo story called “Thirty Koku,” referring to the size of passenger boat which travelers commonly rode to get to or from Kyoto and Osaka via the Yodo River. The storyteller, in providing original and amusing talk to lead into the story, will often explain about the uppermost point of the boat’s course, which is the bridge called Sanjo-ohashi, in the middle of Kyoto. Some storytellers mention many of the famous spots that Kyoto visitors of yesteryear may have planned to visit; spots which are popular Kyoto attractions to this day.

Gretchen Mittwer

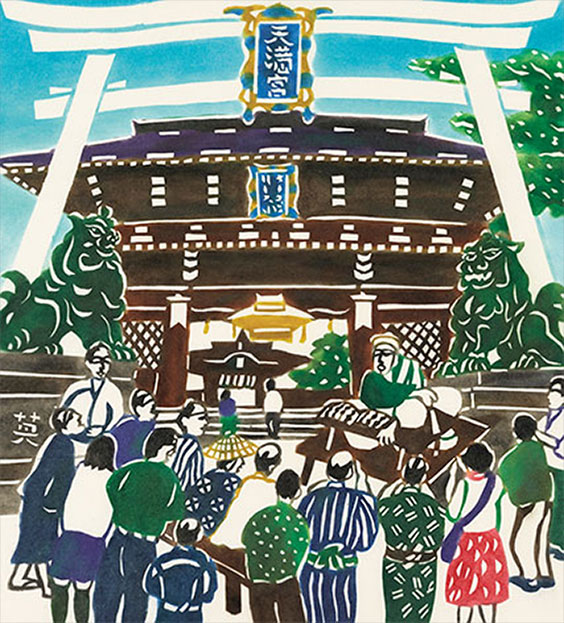

Cover:Kitano Tenmangu Shrine in Rakugo History

The cover art represents a place associated with the early history of Kamigata Rakugo, the Rakugo tradition of the Kyoto-Osaka region. A crowd is gathered around a Rakugo storyteller performing on an open-air platform in front of Kyoto’s Kitano Tenmangu Shrine, with script book open in front of him. The scene when Tsuyu no Gorobei, in the 1680s, would come and entertain people with his amusing storytelling may have been a lot like this. Great throngs visit Kitano Tenmangu on festival days, largely attracted by the vendors of all sorts, and the entertaining street performances they might come across. Tsuyu no Gorobei’s storytelling activities have made him known as the founder of Kamigata Rakugo. And, no kidding, he was a Buddhist priest of the Nichiren sect.

January - February:“The ‘Humm?’ Tea Bowl”Kiyomizudera Temple’s Otowa-no-taki Waterfall

So, on the January-February page, we begin with the story, “The ‘Humm?’ Tea Bowl,” which takes us to the Otowa-no-taki Waterfall at Kiyomizudera Temple. The story opens with Kyoto’s top appraiser of tea implements, who has the nickname “Tea Gold,” drinking tea at a refreshment shop by the waterfall. Finishing the tea, he examines the bowl it was served in with great thoroughness, tilts his head, and murmurs “Humm.” Observing this is “Oil Vendor.” After Tea Gold leaves, Oil Vendor buys the tea bowl from the shop for two gold coins, all the money that he has. He takes it to Tea Gold’s store and offers to sell it for a thousand gold coins, but Tea Gold tells him that, though the bowl has no flaws, it leaks and is hardly worth anything. The ensuing twists in the plot tell how Tea Gold takes pity on Oil Vendor, and manages to get some elite prestige added to the bowl. The Emperor’s Councilor composes a poem for it which alludes to the Otowa-no-taki, and the bowl’s box receives the imperial inscription, “Humm.” The bowl thus finds a buyer for a thousand gold coins.

March - April:“Mount Atago”Mount Atago

For the March-April page, we are at Mount Atago, where a gentleman of the sort called a danna ― a man of means who typically enjoys such amusements as partying with maiko and geisha ― brings a small group of playful maiko and geisha on a hiking excursion. It is an arduous climb up the mountain, and the main character in this story, a male geisha named Ippachi, goes through various comical trials in keeping up with the energetic others. At the resting point halfway up the mountain, there is a shop that sells small bisque ware saucers for hikers to toss into the deep valley below, for fun. The danna is adept at this, but Ippachi, to his own chagrin, fails sadly. Ippachi’s excuse is that where he is from, Osaka, people toss coins, not saucers. Surprisingly, the danna has 20 rare gold coins readied for just this, and tosses them into the valley. Whoever eventually finds them can have them, he says. Ippachi, eager to have them, borrows a large umbrella from the shop, thinking he can use it to parachute down. After getting a push from behind, he lands amid the patch of gold coins. He calls out his success in finding all 20 coins. The danna calls out, “Good! And now, what’s your plan for getting back up here?” Ippachi thinks, “Yikes!” He is quick-witted, however. Ingeniously, he tears up his silk undergarment to make a long rope, ties a rock to one end and flings it up so the rope latches onto a bamboo growing on the mountainside, pulls the bamboo into a taut bow, lets it loose, and lands back with the others in one amazing swoop. The danna is impressed, and enquires about the gold coins. “The gold coins? Yikes, I forgot them down there!” So ends this comical tale.

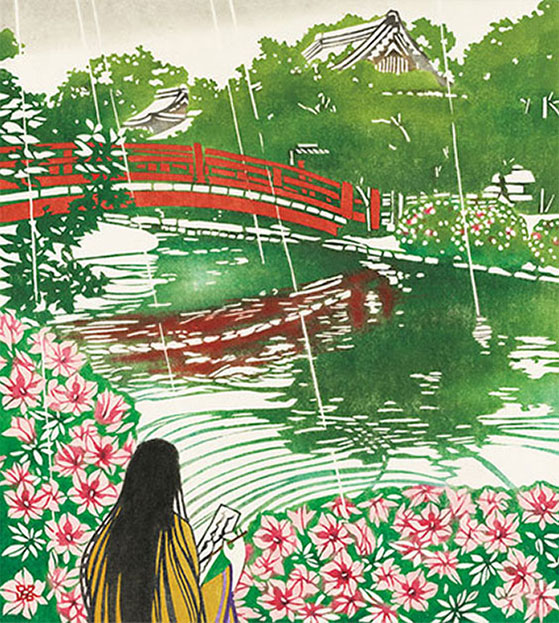

May - June:“Wordplay Komachi”Shinsen’en Garden

The May-June site is the ancient imperial garden called Shinsen’en, and the story title might be rendered as “Wordplay Komachi,” Komachi being the famous ancient poetess, Ono-no-Komachi. This relatively modern story takes place wholly in Osaka, and has Kanbei calling on Sasuke. Sasuke’s disgruntled “ol’ lady” is a woman packed with silly yet amazing verbal dexterity and little sophistication. She tells Kanbei that her good-for-nothing husband is out and has secretly been patronizing a young woman belonging to a tea house in the pleasure quarter. She describes how she tailed him there, barged into the tea house, dragged him home, and gave him an earful. Kanbei offers her suggestions as to how to win Sasuke’s devotion. She should treat him tenderheartedly, and develop tact and finesse in her way of communication. Kanbei brings up the example of Ono-no-Komachi’s effective rain prayer poem composed at Shinsen’en, a poem containing eloquent plays on words. Sasuke’s ol’ lady promptly dives into a nonsensical tirade using all manner of wordplay.

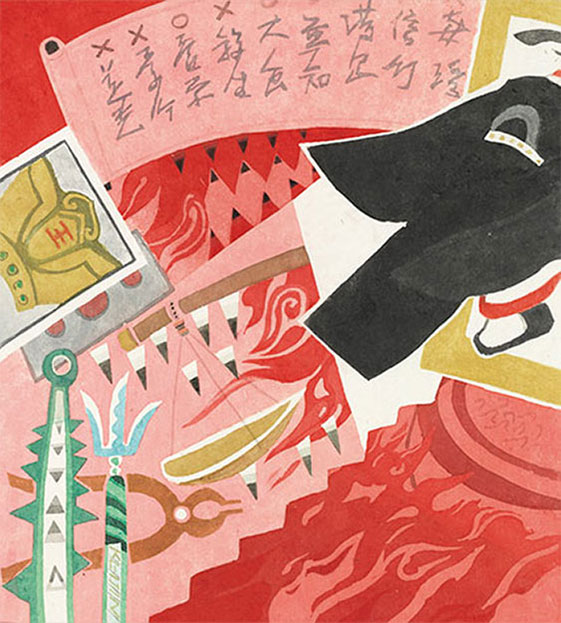

July - August:“Ghost Candy”Rokudo Chinnoji Temple

For July-August, the story is “Ghost Candy.” It is the year 1599, and the site is Rokudo Chinnoji Temple, believed to stand at the border between this world and the afterworld. One night, a pale woman appears at the candy store in front of the temple, to buy a piece of candy with the one-mon coin she has. This happens for six nights straight. On the seventh night, she is without money. The storekeeper gives her the usual piece of candy, and decides to follow her. She enters the graveyard at Kodaiji Temple and disappears. From a grave, however, a baby can be heard crying, so the storekeeper excavates the grave and is able to save the baby. The woman had been pregnant when she died, and had somehow given birth after she had been laid to rest. Six one-mon coins had been placed in her coffin, as fare for the boat which would take her across the river to the afterworld. She had used them for the candy she bought to feed her baby. It was a little boy, who grew up to become a priest at Kodaiji. “Ko o daiji.” (This short last phrase, nearly a homophone for the temple name, means “to lovingly caring after one’s child.”)

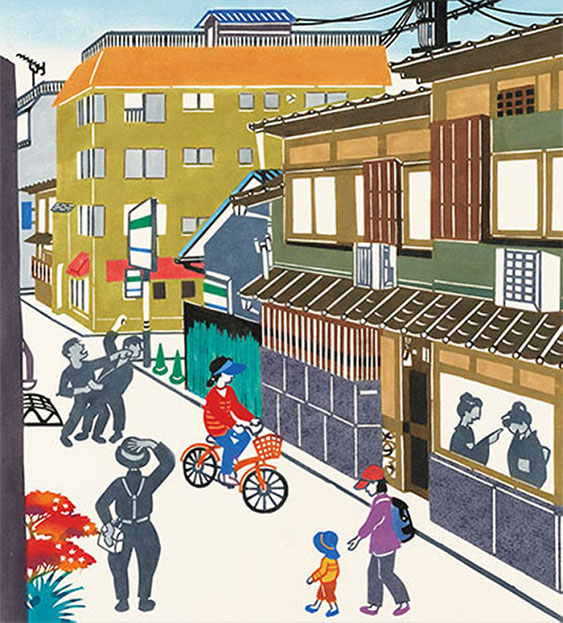

September - October:“Hip-pouch Kosuke”Yanaginobanba-Oshikoji Area

The September-October story, “Hip-pouch Kosuke” (alternately, “Commotion Kosuke”), is about Kosuke, a super-earnest bloke who has made a life for himself in Osaka as a log splitter and enjoys his reputation as a quarrel mediator. He hasn’t a clue about popular amusements. His single joy lies in stepping in when people are quarreling, and pacifying them. He is known to often go all-out in treating quarrelers to food and drink, over which they can mend their differences. A couple of chaps know this, and rig a fight together, aiming for Kosuke to step in. This somehow works out for them. Kosuke, always on the prowl for a quarrel, hears the shouts and pleas of two women. Eager to intercede, he innocently comes into a lesson room where amateurs are practicing the art of dramatic storytelling. The dramatic recitation he overheard was a short bit from a popular story in which, at an old obi shop near the corner of Yanaginobanba and Oshikoji in Kyoto, the wife of the proprietor suffers outright bullying by her oppressive mother-in-law. The lesson room mistress explains about the place and characters involved in the story, but Kosuke can’t get it through his thick skull that the characters and squabble are make-believe. He jumps onto the overnight boat to Kyoto and finds his way to Yanaginobanba Oshikoji. There just so happens to be an obi shop right there. Although Kanbei’s explanation of who he needs to see makes no sense to the shop manager, Kanbei learns that the two women who possibly match the description are dead. He jumps to the conclusion that, regretfully, he was a day late in stopping them from killing each other.

November - December:“Thirty Koku”Sanjo-ohashi Bridge

"The inspiration for the November-December page is the classical Rakugo story called “Thirty Koku,” referring to the size of passenger boat which travelers commonly rode to get to or from Kyoto and Osaka via the Yodo River. The storyteller, in providing original and amusing talk to lead into the story, will often explain about the uppermost point of the boat’s course, which is the bridge called Sanjo- ohashi, in the middle of Kyoto. Some storytellers mention many of the famous spots that Kyoto visitors of yesteryear may have planned to visit; spots which are popular Kyoto attractions to this day. "