2016 calendarKyoto’s Sacred Protective Creatures

SCROLL

This year’s calendar focuses on a selection of the protective creatures that are distinguishing features of the age-old Shinto shrines, Buddhist temples, and festivals which are essential elements of the cultural make-up of the intriguing city of Kyoto. Among those creatures, there are real kinds of animals, and there are fantastic animals born of the rich imagination of the ancients.

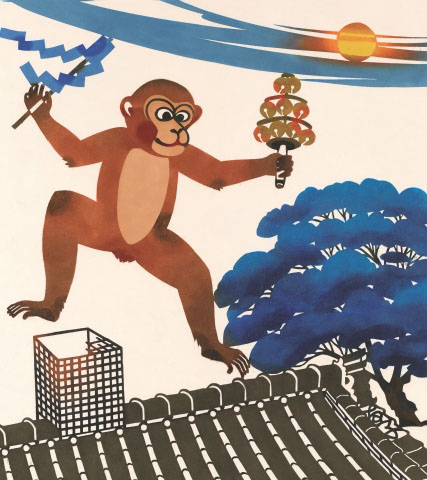

Proceeding one by one through the calendar, we have on the cover a portrayal of a monkey holding a Shinto bell instrument in one hand and a Shinto wand with sacred paper streamers in the other. It is the monkey of Sekizan Zen’in, a Tendai-sect Buddhist temple located near the base of Mount Hiei in the northeast corner of Kyoto city. To unravel the whys and wherefores about this monkey begs mention that there are many traditional beliefs and practices in Japan which combine 1) the indigenous Shinto tradition, which is largely based in a belief in sublime spirits in and of nature which have the power to either wreak havoc on or protect the people, 2) the Buddhist religion, which has its roots in India and entered Japan from China, and which in essence leads humans to recognize and free themselves from the seeds of the problems of human existence which cause them suffering, foremost of which are egotism and greed, and 3) deep beliefs based in Chinese geomancy. This does not end the list, but as far as our story of the monkey goes, we have the fact that, according to Chinese geomancy, the northeast is the most ominous direction, from which evil forces attempt to enter through the front ”devil’s gate.” When the Kyoto basin was chosen as the site to create the new ‟Capital of Peace” over twelve hundred years ago, and the city plan was designed, this belief in Chinese geomancy was at work. The move of the capital to this location was prompted by calamities which had befallen previous seats of the emperor. The Kyoto basin is fortified by mountain ranges on the north, east, and west, and the prominent mountain peak in the northeast is Mount Hiei, where many monkeys can be seen even today. Between Mount Hiei and the northern mountains is a narrow pass. It so happens that the Japanese word for “monkey” has the same pronunciation as that meaning “go away,” and so the monkey was considered the protector god of Mount Hiei. At the Shinto shrine on Mount Hiei, this animal represents the protector spirit known as the “demon queller.” The summit of Mount Hiei is home to the Buddhist Tendai sect head temple, Enryakuji, built in the Enryaku era (782–805) to protect the Imperial Palace against the noxious influences of the northeast. Among the temples belonging to it, there is Sekizan Zen’in, situated in a direct line between the northeast corner of the Imperial Palace and the dreaded front “devil’s gate.” The wall enclosing the Inner Palace, where the Emperor and his court resided, has in its northeast corner a statue of a monkey which faces the monkey statue on the roof of the Shinto style prayer hall at Sekizan Zen’in, and these two monkeys theoretically see and protect the entire intervening area.

Another real animal that lives in the wild in Japan is the boar, the protector animal of Go’o Jinja, the “Shrine of the Protector of the Emperor,” situated across the street along the western side of the Kyoto Imperial Palace. Instead of the usual mythical guardian lion-dogs which stand outside most Shinto shrines, this shrine, dedicated to Lord Waké no Kiyomaro (733–799), uniquely has a pair of wild boar. There are numerous images of wild boars of all sizes within the compound, as well. In 769, Kiyomaro distinguished himself by suppressing a rebellion and thwarting evil designs on the throne. He was also influential in the emperor’s decision to move the capital to Kyoto. At one point in his career, however, he was exiled for having displeased the empress. As legend has it, he injured his leg en route to his place of exile, but was miraculously saved by three hundred wild boars which appeared to protect him, and his leg also healed. Owing to this legend, Go’o Jinja is visited by many pilgrims who come to pray to the deified Waké no Kiyomaro and seek cure for leg illnesses.

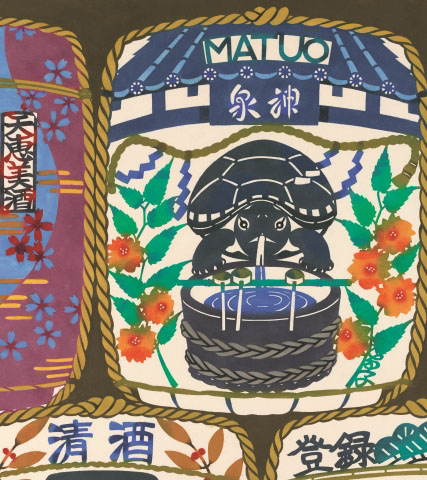

Longevity is something that humans naturally aspire for, and the tortoise is a traditional symbol of longevity. At Matsuno’o Taisha, the dominant Shinto shrine in the western part of Kyoto city, this self-protected, unhurried creature is especially prominent. According to the shrine lore, the lord of the Hata clan — a clan said to have had its origins in a Korean prince who came to Japan early on, and which inhabited the Kyoto basin long before the establishment of the Heian capital — was riding in the area one day and saw a tortoise bathing at the base of the waterfall flowing down from Mount Matsuno’o, where resided the god of large mountains, and this auspicious encounter inspired him to create this shrine. This predates the establishment of the Heian capital by nearly a century. Among the contributions of the Hata clan to Japanese culture, they introduced a new saké (rice wine) brewing technique, and the spring water at this shrine, blessed by the tortoise, is believed to hold the power to keep saké from going sour. Hence, Matsuno’o Taisha has been widely known as the home of the god of saké brewing.

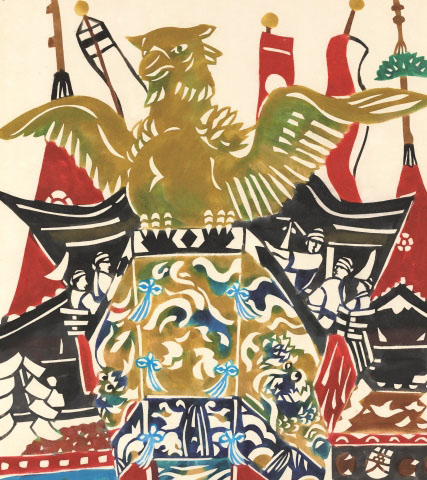

Together with the tortoise, the fantastic bird known as the Ho’o or Phoenix, considered the emperor of all birds according to Chinese legend, is one of the four legendary creatures which guard the four cosmic directions. Crowning the roof of the elegant “Phoenix Hall” housing the awe-inspiring golden image of Amida Buddha at Byodoin temple in the south of Kyoto is a pair of phoenixes. This hall is well-known for its being the design on the ten-yen coin minted since 1951. It is said to have the shape of a phoenix with wings spread and tail extending to the rear. The hall, fronted by a mirror-like pond on the east, was created as a vision of the Buddhist Western Paradise.

Another mythical bird which the Japanese adopted from China long ago is the Geki, an imaginary water bird that soars high in the sky and also dives into water. For these properties, it was used as the figurehead on the prow of boats which court nobles enjoyed riding for elegant recreation during the days of the ancient capital. The main focal points of Kyoto’s time-honored Gion Matsuri festival which attracts tens of thousands of visitors each year are the huge floats called hoko. These structures are dismantled and put up again each year, and are like museums in themselves for their priceless decorations which have come down through time thanks their preservation by the local community. Among the historical floats was one in the shape of a large wooden ship, with elaborate Geki decorating its prow, but which unfortunately was lost by fire years ago. In 2015, it again could be seen in all its original grandeur, owing to the efforts of many people, including those at the frontline of modern technology in order to faithfully reconstruct the float.

In the scenic area of Arashiyama in western Kyoto, there is the impressive temple called Tenryuji, or “Temple of the Heavenly Dragon,” nestled at the foot of Kameyama, “Tortoise Hill.” It is the head temple of the Tenryuji branch of the Rinzai Zen sect, and was founded in 1339 by the venerated priest, Muso Soseki. The dragon is another fantastic creature which found its way to Japan from China. It symbolizes power, creativity, heaven, and water, and in Zen, it appears as a symbol of enlightenment. The beautiful garden beyond the main building at Tenryuji centers on a pond, to the far side of which there is a beautifully designed waterfall, the “Dragon’s Gate Waterfall,” dropping down from “Tortoise Hill.” It is said that, at the time of Tenryuji’s founding, Mount Hiei monks opposed to its opening disrupted its dedication, and Muso had this to say about the situation and those riotous monks: “Although three thousand monkeys are screeching . . . the dragon sleeps on tortoise hill.” Another dragon-related feature at Tenryuji is the bold, monochrome painting of a dragon amid clouds on the ceiling of the lecture hall. The painting is designed so that the dragon appears to face you no matter where you stand.

At the end of our calendar journey this year, during which we have looked at some of the protective animal figures one might come across in Kyoto, we find ourselves at Yasaka Shrine, the Shinto shrine familiarly referred to as “Gion-san.” It is located in Kyoto’s famed Gion district, and is the shrine around which the Gion Matsuri revolves. Guarding the main gate here is the pair of guardian lion-dogs known as komanu — creatures which are commonly seated at the entrance of Shinto shrines and Buddhist temples everywhere in Japan. One has mouth open and the other has mouth closed, as the pair voice the first and last syllables of the Sanskrit alphabet, the same as the Japanese alphabet, “Ah-um,” representing the beginning and end of all things.

Gretchen Mittwer

Cover:The Monkey of Sekizan Zen’in Temple

On the cover of this calendar is a rather comical-looking monkey leaping through the air, with the morning sun rising behind him to the east. It is the ceramic monkey perched atop the roof of Sekizan Zen’in temple come to life, to look over the city of Kyoto — particularly the Imperial Palace — from the northeast and guard it against evil forces attempting to enter from that ominous direction referred to as the “demon’s gate.” Monkeys have been the subject of lore from ancient times, not only in Japan. In that the word for “monkey” is a homonym for “go away” in the Japanese language, however, this anthropoid inhabiting the wilderness around Kyoto’s “demon’s gate” assumed a special role, as guardian and protector at that gate. The monkey in the calendar picture holds symbols of his Shinto sanctity and power to rid evil. Sekizan Zen’in temple is straight northeast of the Kyoto Imperial Palace, and at the northeast corner of the wall enclosing the Inner Palace is a monkey figure facing the one at this temple. Together, they protect the intervening land.

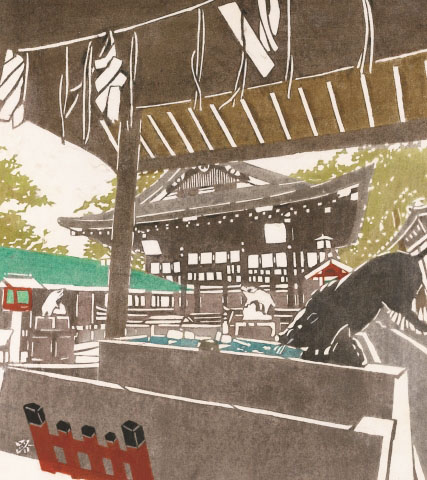

January - February:The Wild Boars of Go’o Shrine

The art work on this page was created for this calendar by Kyoto textile artist Michiko Kasugai, using dyes on cloth. The scene is of Go’o Jinja, the “Shrine of the Protector of the Emperor,” a Shinto shrine unique in its adoption of the wild boar as its protective animal. This shrine is dedicated to Lord Waké no Kiyomaro (8th c.), honored for his valor in protecting the Emperor and the imperial regime. Legend says that Kiyomaru was mirac-ulously saved and cured of a leg injury by a great pack of wild boars at one critical point in his illustrious career.

March - April:The Tortoise of Matsuno’o Shrine

The art work on this page was created for this calendar by Kyoto textile artist Keiko Kanesaki, using dyes on cloth. The design is of stylized saké barrels, the main one of which is decorated with the legendary tortoise of Matsuno’o Shrine’s “water well of the tortoise.” The tale about the spring water welling forth here, blessed by the auspicious tortoise, has made Matsuno’o Shrine known as the home of the god of saké brewing. Breweries come to pray here, and the shrine features is a grand display of saké barrels, the inspiration for the calendar picture.

May - June:The Phoenix of Byodoin Temple

The art work on this page was created for this calendar by Kyoto textile artist Keijin Ihaya, using dyes on cloth. Swooping across is a phoenix, the mythical emperor of all birds, and floating on clouds are a figure playing music and another holding an important article for man to reach the Buddhist Pure Land, as decorate the “Phoenix Hall” of Byodoin Temple. Byodoin was created in the year marking the onset of the decline of the world according to the Buddhist scriptures, and the “Phoenix Hall” repre-sents a vision of the Western Paradise, the Pure Land.

July - August:The Geki Bird of the Gion Festival“Boat Float”

The art work on this page was created for this calendar by Kyoto textile artist Naito Hideharu, using dyes on cloth. The bird commanding the scene is the figurehead of one of the grand floats — the newly resurrected Fune-hoko or “Boat Float” — of Kyoto’s famous Gion Festival, a Shinto festival originating in 869 to seek divine help to relieve the people from the terrible ills they were suffering. The bird is a Geki, a mythical white bird adept at flying as well as diving. It is a protective creature traditionally used on the prows of boats associated with imperial authority.

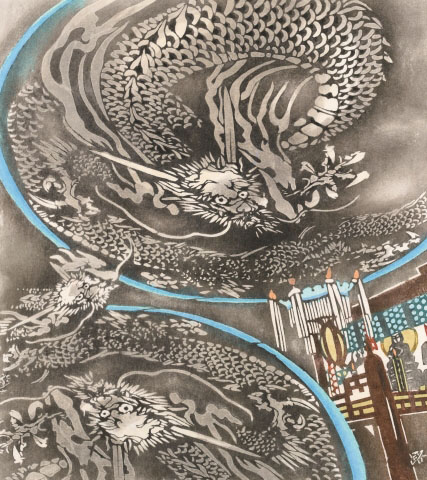

September - October:The Dragon of Tenryuji Temple

The art work on this page was created for this calendar by Kyoto textile artist Michiko Kasugai, using dyes on cloth. It stylistically portrays the great dragon painted on the ceiling of the lecture hall at Tenryuji, “the “Temple of the Heavenly Dragon,” which appears to be staring at you wherever you are. The king of mythical creatures, the dragon is a symbol of power, creativity, heaven, and enlightenment, and holds control over water. Among the reasons for its being the motif on the lecture hall ceiling is that it protects this important structure from fire.

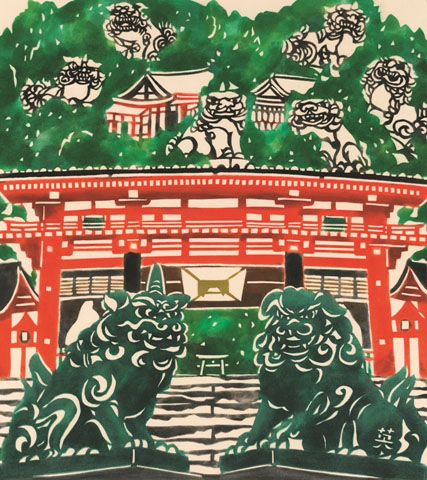

November - December:The Lion-dogs of Yasaka Shrine

The art work on this page was created for this calendar by Kyoto textile artist Hideharu Naito, using dyes on cloth. It shows Yasaka Shrine, with its familiar vermillion gate, in Kyoto’s famous Gion district downtown, and in front are its guardian lion-dogs at the foot of the stairs to the gate. The mythical lion-dog is often the protective creature which stands or sits guard at entrances. As a pair, one conventionally has mouth open and the other, closed, signifying their voicing of the first and last syllables of the alphabet, or the beginning and end of all things.