2024 calendarThe Mountain Scenery of Kyoto

SCROLL

Whichever direction one turns one’s gaze in the city of Kyoto, scenic mountains meet one’s eyes, for Kyoto lies in a basin surrounded on three sides by its Higashiyama, Kitayama, and Nishiyama mountain ranges―that is, its “Eastern Mountains,” “Northern Mountains,” and “Western Mountains.” These have provided a natural fortress, while also being behind the city’s atmospheric conditions and dramatic seasonal changes.Famously, Kyoto’s winters are penetratingly cold, and summers are stiflingly hot and humid, with little wind-flow to offer relief.Equally famously, however, the scenic sites in and around the city are strikingly beautiful, and what gives them their unique depth and allure is the history and traditions entwined in them.

This year’s calendar takes us on a visit to a few of the mountains which make up the scenery of Kyoto. On the cover is Mount Atago, the northernmost of the nineteen peaks of the “Western Mountains,” and the highest mountain in the city, standing at a height of 924 meters above sea level. This is about 76 meters taller than its rival, Mount Hiei, the northernmost of the thirty-six peaks of the “Eastern Mountains” on the opposite side of the city.

There is a humorous anecdote concerning this. It seems that the Western and Eastern ranges were vying to decide which of them was higher, but no matter how many times they measured, the result was inconclusive. Alas, their arguing led to Mount Hiei giving Mount Atago a mighty smack on top of his head, and the resulting lump that Mount Atago developed consequently made him the winner. And indeed, the silhouette of Mount Atago reveals a large bump on its summit.

This Mount Atago was once known by the name Asahi-ga-oka, meaning “Hill of the Morning Sun,” in that this was the first spot in the capital on which the morning sun shone. Throughout the history of Kyoto, this mountain has been regarded as an important power spot. (See COVER explanation.)

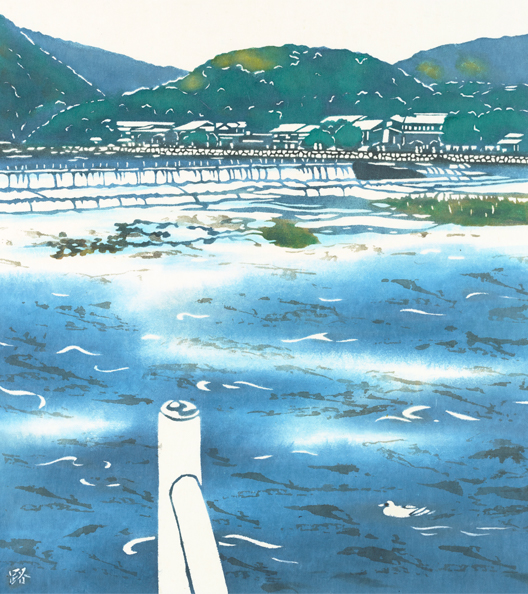

The mountain taken up on the September-October page is Mount Ogura, lying in the same corner of Kyoto as Mount Atago. It is a graceful hill on the northern side of the Hozu River gorge, with the Arashiyama, or literally “Storm Mountains,” standing across from it on the gorge’s southern side.

Though Mount Ogura is only 296 meters high, it figures prominently in the history of classical waka (Japanese-style poetry), and is known as “poet’s mountain.” Heian period (794-1185) emperors and courtiers loved this area as a place to compose verses about the four seasons, and most famously, it was here that the influential waka master Fujiwara no Teika (1162-1241) put together his “One Hundred Poets, One Poem Each” collection, selecting one poem for each of the one hundred most celebrated poets of his time, and writing them out on poem paper to decorate his country home at Mount Ogura. Later, haiku poet Matsuo Basho (1644-94) wrote his “Saga Diary” at the foot of Mount Ogura. Today, people with an interest in Japanese literature journey to Mount Ogura from all parts of Japan and around the world, to compose their own haiku or simply to enjoy the impressive scenery along the hiking trails.

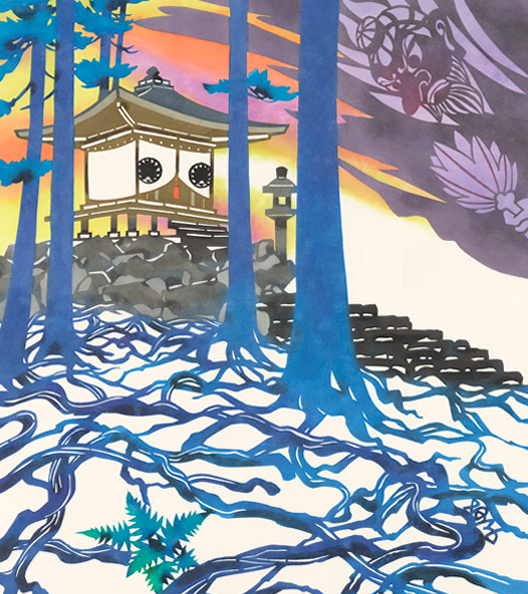

Leaping to the opposite corner of Kyoto, there is the mountain featured on the November-December page, Mount Kurama, situated deep within the northeastern reach of the city. If one traces Kyoto’s famous Kamo River upstream to its source, there is the tributary named Kurama River, which changes name to Kibune River as it winds its course at the foot of the sacred Mount Kurama. The mountain air here, amid the towering cedars, is crisp and fresh, and the waters are ice-cold and crystal-clear. One senses a mystical power innate at this place.

Midway up Mount Kurama is Kurama Temple, and along the way to the its inner sanctuary, there stands the hall shown on the November-December page. It is dedicated to the deity “Mao,” the “Spirit King of Mother Earth,” who is said to have descended to Earth from Venus some six million years ago. Around this remote area, Ushiwakamaru―the famous warrior Minamoto no Yoshitsune (1159-89) in his boyhood days, when he was a foster acolyte at the temple―is famously said to have been taught the art of sword-fighting by Kurama Tengu, the “heavenly creature” of Kurama.

The small town of Kurama, known for its hot springs, lies in the valley between Mount Kurama and Mount Hiei, that mountain rival of Mount Atago which we came across earlier, and which is the mountain for the March-April page. According to the fūsui (Ch., feng shui;lit., “wind-water”) laws of geomancy which guided the choice of the Kyoto basin as the site for the Capital of Peace (Heian-kyō, the original name for Kyoto), this whole area, including Mount Kurama and Mount Hiei, lies in the ominous direction of the “devil’s gate” (kimon)―the Northeast, from which malevolent powers could enter and cause havoc. Many of the Shinto shrines and Buddhist temples in Kyoto were established to protect the capital from such malevolence.

Mount Hiei actually straddles the border between Kyoto and Shiga prefectures, and its expansive Hiyoshi Grand Shrine, though situated on the Shiga side, was an important protector shrine of Kyoto, enshrining the Shinto deity Ōyamakui, “Owner of the Big Mountain.”

Together with Mount Hiei’s Shinto significance, there is its immense importance as the home of Enryaku-ji temple, the headquarters of the Tendai school of Buddhism in Japan, founded in 788 by Saicho. For Emperor Kammu (r. 782-806), in search of the perfect site to build his new Capital of Peace, the presence of Saicho and his “new Buddhism” on Mount Hiei was seen to provide the vital protection needed in this devil’s gate direction. He placed his trust in Saicho and the new Buddhism practiced at Saicho’s monastery, and once he and his court officially moved to the new Capital of Peace in 794, Enryaku-ji’s prestige rose by leaps and bounds as the temple enjoyed the patronage of the emperor.

Today, the grounds of this monastery complex cover roughly 1,700 hectares, or 4,200 acres, of forest atop Mount Hiei. In the main hall, designated a National Treasure and called Konponchūdō, reside the statue of Yakushi Nyorai, the “Healing Buddha,” that is said to have been created in 788 by Saicho himself, and the “eternally burning light” that burns in front of the statue, said to originate from the offering of light that Saicho made to the “Healing Buddha” at that time, 1,200 years ago. The artwork on the March-April page is of the altar which houses these.

Turning our eyes southward from Mount Hiei, there is Mount Uryū, featured on the May-June page. This rather remote mountain is the site of numerous legends related to the healing of illnesses and longevity. Many have to do with the deity Gozu Tenno, to whom Kyoto’s famous Gion Yasaka Shrine is dedicated, and who thus factors largely in Kyoto’s time-honored Gion Matsuri festival held in July, which attracts hundreds of thousands of people.

One is not likely to come across any crowds along the rugged hiking trails through Mount Uryū, which offer nature lovers delightful scenes of wildflowers of the season, as well as evidence of Kyoto’s not always peaceful history, particularly during the Sengoku or “Warring States” period (1467-ca. 1590), a period of chronic conflict between territorial lords in areas around the country, vying for wider control. The building shown in the artwork is the small shrine that sits at the summit, at a height of 294 meters above sea level, on the site where there once stood Mount Uryu Castle, built in 1527 and occupied by several generals, but finally abandoned once the great warrior Oda Nobunaga established control of Kyoto in 1571. There is a mystical atmosphere in these parts, represented by the deities seen floating about the shrine in the May-June page artwork.

Mount Nyoigatake, the second most predominant peak of the “Eastern Mountains,” standing at a height of 459 meters, is the focus of the July-August page. The Temple of the Silver Pavilion, Ginkaku-ji, which the shogun Ashikaga Yoshimasa originally built in 1460 as his retirement villa, is nestled within its skirt. This villa of Yoshimasa’s was a cultural center from which flowered the arts of chanoyu, flower arrangement, poetry, and noh theater. The culture that flourished here during Yoshimasa’s day, and which may be said to have set the tone of those traditional art forms which are so representative of Japan, is known as Higashiyama Culture.

For most people, however, the part of Mount Nyoigatake that comprises Mount Daimonji (lit., “mountain of the character ‘big’”) is particularly familiar, because of its prominence in Kyoto’s awe-inspiring “farewell bonfires” ceremony held annually on the night of August 16. The ceremony is the culmination of the Buddhist Obon period, during which the spirits of the ancestors were able to come home to their families. On this final night, bonfires in religiously symbolic shapes are lit on five of the mountains surrounding the northern part of the city, to send the spirits back to the other world. On the face of Mount Daimonji, a huge character “大”, meaning “big”, burns bright in the dark night. Once it begins to burn, the bonfires are ignited on the other mountains, and at the highpoint, all the fires are burning brightly, while the people watch and bid farewell to their ancestors.

The last of this calendar’s mountain visits is to Mount Inari, at the southernmost end of the Eastern Mountains. This whole mountain area comprises the sacred grounds of Fushimi Inari Shrine, which was originally built by the prosperous Hata clan that inhabited this region prior to the establishment of the Capital of Peace. The shrine is dedicated to the deity of agriculture, and also the deity of commercial prosperity.

The process of walking around to the three peaks of Mount Inari, a course of roughly 4 kilometers, is a sort of religious exercise, and people refer to it as “oyama wo suru,” or “to do the respected mountains.” It begins by entering the shrine’s spectacular “tunnel of a thousand torii gates.”

Thus, as has been briefly introduced in this essay, the mountains which surround the Kyoto Basin embrace the history of Kyoto, and throughout time, have shaped the way in which the people have lived their lives.

Gretchen Mittwer

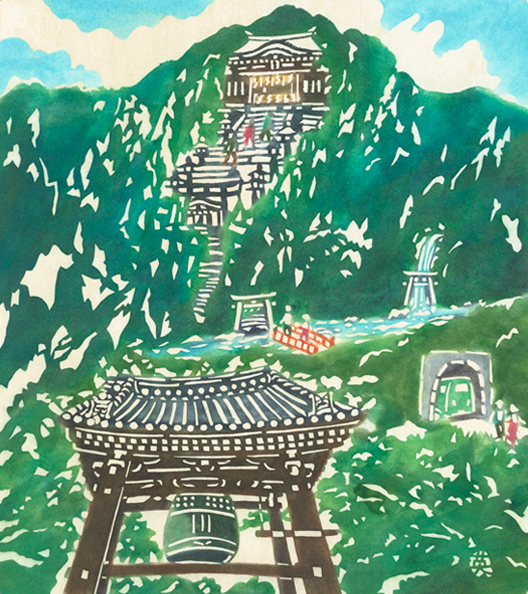

Cover:Mount Atago

At the summit of Mount Atago sits Atago Shrine, a prayer site which is believed to offer protection against fire disasters. The shrine traces its origins to the beginning of the 8th c., when the founder of the Shugendo “mountain asceticism” religion of Japan, together with the Shugendo monk Taicho, erected a shrine at this remote mountaintop spot. Ever since, Mount Atago has been a pilgrimage center for Shugendo followers. While the shrine is dedicated to several Shinto deities, or kami, who feature in Japan’s mythological tale connected with Kagutsuchi, the deity of fire, the main figure of worship is Atago Daigongen, the fire protector. Given that fire was a major concern in the everyday lives of the people, who lived in highly flammable structures, this shrine has been held in deep regard, and many hundreds of people make the annual nighttime pilgrimage that takes place from the evening of July 31 to the early morning of August 1 and is said to provide a thousand days of protection. The pilgrims receive an amulet and sacred branch of Japanese star anise, to place in the Shinto altar at home. If, by the age of three, a child is carried on its parent’s back to make a pilgrimage, it is said that the child will be protected from fire throughout its life.

January - February:Mount Inari

The artwork, by the textile dyeing artist Michiko Kasugai, is of the “tunnel of a thousand torii gates” of Fushimi Inari Shrine, which is located at Mount Inari and is one of Kyoto’s most popular sightseeing attractions. The sacred grounds of this shrine encompass Mount Inari, the southernmost peak of Kyoto’s “Eastern Mountains,” and a thorough visit entails passing through the torii tunnel and walking around the 4 km mountain path circuit, where there are sub-shrines. The torii are donations from patrons, who pray for a good harvest and business prosperity.

March - April:Mount Hiei

The artwork here, by the textile dyeing artist Keijin Ihaya, is of the altar within the main hall of Enryaku-ji Temple, on the summit of Mount Hiei, the northernmost peak of Kyoto’s “Eastern Mountains,” and second-highest mountain of Kyoto city. The altar houses the statue of Yakushi Nyorai, the “Healing Buddha,” said to have been created in 788 by Saicho, when he established his monastery here, and the “eternally burning light” that burns in front of the statue said to originate from the offering of light that Saicho made to the “Healing Buddha” at that time.

May - June:Mount Uryū

The artwork, by the textile dyeing artist Keiko Kanesaki, is of the small shrine on Mount Uryū, in the vicinity of one of the three main passes leading across the “Eastern Mountains.” In bygone days when Kyoto was often threatened by attack from warlords seeking to gain government control, outposts and castles were built, and were the scenes of fierce battles. Mount Uryū Castle stood at the site of the depicted shrine. It was founded in 1520 and occupied by several generals, but finally abandoned once the great warrior Oda Nobunaga won control of Kyoto in 1571.

July - August:Mount Nyoigatake

The artwork, by the textile dyeing artist Hideharu Naito, shows Mount Nyoigatake, the second tallest peak of Kyoto’s “Eastern Mountains.” The part of Mount Nyoigatake called Mount Daimonji, “mountain of the character ‘big’,” has a clearing where the character “大” (dai, “big”) can be seen. It plays the leading role in the “farewell bonfires” ceremony of August 16, culminating the Buddhist Obon period. On this night, bonfires in symbolic shapes are lit on five mountains, to send the spirits of the ancestors back to the other world. The “大” bonfire here leads it off.

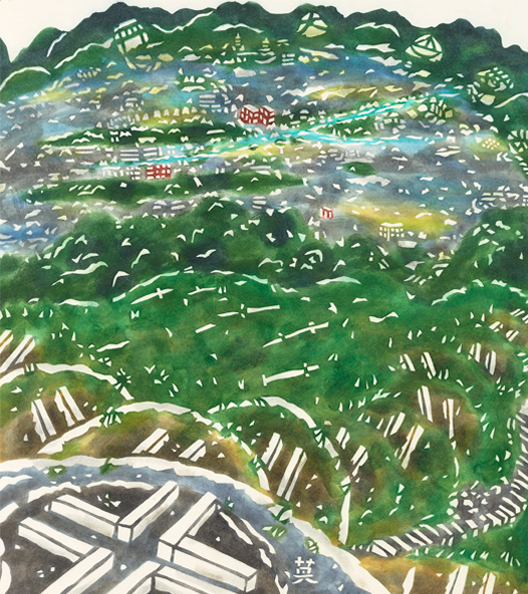

September - October:Mount Ogura

The artwork, by the textile dyeing artist Michiko Kasugai, shows Mount Ogura, fondly known as “poet’s mountain,” as seen from across the Hozu (Katsura) River in the northeastern corner of Kyoto. Throughout the ages, it has captured people’s hearts for its exquisite scenery. Famously, it was here that the courtier Fujiwara no Teika (1162–1241) put together his “One Hundred Poets, One Poem Each” collection, which includes this poem: “Autumn leaves on the peak of Mount Ogura. If you possess a heart, please wait as you are now until the emperor comes to visit once again.”

November - December:Mount Kurama

The artwork on this page is by the textile dyeing artist Keiko Kanesaki. Kyoto’s “Northern Mountains” stretch far into the north, dipping and rising like waves as they reach the Tamba plateau. At their eastern end is Mount Kurama, dense with towering cedars and rich in legendary tales. It is, for instance, the home of Japan’s well-known Tengu, or “heavenly creature” with red face and long nose. Midway up this mountain is Kurama Temple, and along the way to its inner sanctuary is the hall depicted here, which is dedicated to “Mao,” the “Spirit King of Mother Earth.”