2018 calendarAn Indelible Mark Left by

Women of Ancient Kyoto

SCROLL

This year’s calendar takes us to seven temples and shrines in Kyoto associated with women in the cultural history of Japan. By knowing something about the heroines of this calendar and imagining their situations in life, our casual visit to these temples or shrines assumes the nature of a historical novel and brings alive the subtle colors of the fabric which makes up the cultural allure of Kyoto.

We are taken to the ancient days of the Heian period (794–1186), when Kyoto flourished as the “Capital of Peace.” The Kyoto world revolved around the affairs surrounding the imperial court, and thanks largely to our heroines, we have insight into the consciousness of those who were right there. Their poems, diaries, and stories, fueling the image of this period characterized by aesthetic aspirations toward refined beauty and courtliness coupled with a deep sensitivity to the melancholic reality of life, bring to light their often agonizing circumstances in their world dominated by men, politics, poetry, love, and whim.

The heroine of the cover page is Murasaki Shikibu (fl. 996–1010), author of The Tale of Genji, considered to be among the world’s finest and earliest novels. Famed though she is, details of her life are obscure, and the name we know her by derives from the heroine of the first two parts her famous novel and her father’s position at the Shikibu, the imperial Bureau of Rites. When she was a child, her father apparently allowed her to study with her brother and even learn some Chinese classics, which was considered improper for females. An account says that her father lamented that he would have been so happy if only she were a boy. Widowed after a brief arranged marriage, she spent the main part of her life as a lady-in-waiting to an imperial consort whose court was a center of literary culture.

The Tale of Genji follows the episodes through life of the novel’s fictitious hero, the “Radiant Genji,” and ultimately tells of the reality that the glories that people idealize and enjoy are but temporary. To quote from the Princeton Companion to Classical Japanese Literature, the author shows “…suffering to be the lot of the most sensitive and powerful of human creatures…, and dreadful misunderstanding of what is important to be the fate of lesser characters.…” The last part of the novel, appropriately, is entitled “The Floating Bridge of Dreams.” According to the modern noh play, “Memorial to Genji,” written by one of the most important Japanese authors of the 20th century, Mishima Yukio (1925–70), Murasaki Shikibui was an incarnation of a certain Goddess of Mercy to teach people the truth that the world is but a dream.

The heroine for the January-February page is Sei Shonagon (ca. 966–1017), a contemporary of Murasaki Shikibu. Shonagon is famed for her witty The Pillow Book, a collection of prose that she jotted in her bedside notebook of her observations of the things around her. She is known to us as Sei Shonagon because of her father’s position as Shonagon, “lesser counselor,” and the term “Sei,” or “Pure,” to distinguish her out of the many people associated with someone of that position. Like so many people of ancient times, it was rank that gave one a name. And like many girl children born into the ranks of the nobility, she became a lady-in-waiting at the court of a consort of the time’s emperor. Her well-known classic, The Pillow Book, moves across a wide range of themes including nature, society, and her own flirtations, and it is through these writings that we form an image of her life and character. To quote from Edwin A. Cranston in the Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan, “Opinionated and abrasive she certainly was, but at the same time possessed of a rare sensitivity to the colors of the passing scene.... She tosses off in passing a few lines on the sheer beauty of icicles gleaming in the moonlight, or the innocent charm of a child eating strawberries, and the images stick in the mind.… She was an original, an author whose unquenchable verve created its own unstructured expression and who shines with unapologetic cheerfulness in a dominantly sad and wistful tradition.”

Predating our previous two heroines is the Heian period beauty and poet, Ono no Komachi (ca. 825―900), for the March-April page. The largely legendary Komachi has left some of the most intense and accessible waka (Japanese poetry), and has been described as perhaps the earliest and best example of a passionate woman poet in the Japanese canon. That she was recognized in her own time as a consummate craftsman of poetry is proven by the fact that she was ranked among the Six Poetic Sages by the compiler of Japan’s first official anthology of poetry. Numerous poems attributed to her are included in various official anthologies. Nearly all are about unhappy love. For example, “Did you come to me because I dropped off to sleep, tormented by love? If I had known I dreamed, I would not have awakened.” (Tr., Steven D. Carter, Traditional Japanese Poetry: An Anthology) Komachi is surrounded by the legend that she had many lovers; stories which inspired many literary works in later ages, including an 11th c. Buddhist treatise, “Book of the Grandeur and Decadence of Tamatsukuri Komachi,” on the impermanence of worldly things, and several classical and still today popular noh plays.

We have for our May-June heroine the court gentlewoman Izumi Shikibu (fl. ca 970―1030), considered not only the most gifted poet of her day but also among the outstanding masters of waka of all time. In addition to her legacy of over 1,500 waka poems, there is her Diary of Izumi Shikibu, a fictionalized version of the love story between her and the great love of her life, Imperial Prince Atsumichi. Brought up at court, she was married twice, and between those marriages was the mistress of two imperial princes. Like Ono no Komachi in an earlier era, she is famous for her intense love poetry. Her poetry shows her to have been possessed of an amorous tendency, and also of a prayerful urge which sought release from the toils of passion through Buddhist en- lightenment and renunciation.

The July-August page focuses on Hokongoin temple and Taikenmon’in (Fujiwara no Shoshi, 1101―1145), daughter of the courtier Fujiwara no Kanezane. As a young child she was adopted by Emperor Shirakawa, and she became the consort of Shirakawa’s grandson, Emperor Toba, with whom she bore seven children. The eldest boy ascended the throne as Emperor Sutoku at age five. Through her short life she was empress consort, empress dowager, grand empress dowager, and in the end, when the retired Emperor Toba took another wife and her life thus took a tragic turn, a nun. This was an era of extreme political maneuvering for power, and the Fujiwara family into which she was born maintained its power over the throne by, for one, its extensive intermarriage with the imperial house. Fated to spend her life as a pawn in this scheme of politics, Taikenmon’in, though she has not come down as a major figure known by most people today, surely left an indelible mark in the cultural history of Kyoto.

Oharano shrine, on the September-October page, is linked to Fujiwara no Takaiko (842–910), who was the official wife of Emperor Seiwa (r. 858–876), mother of Seiwa’s successor, Emperor Yozei, and known after Seiwa’s abdication as the Nijo empress. On the dark side, famous is the affair which she had with a priest named Zenyu, which caused her demotion. More fairytale-like is the story of her romance with the well-known figure in Japan’s literary history, the legendary lover, Ariwara no Narihira. A poem by this woman of dramatic circumstances, the Nijo empress, goes thus: “Spring begins in the midst of snow: perhaps now, at last, the bush warbler’s frozen tears will melt.” (Tr., Frank Watson)

The November-December page, with its imaginative picture of Kuramadera temple, brings us to our last heroine, the beautiful noblewoman Tokiwa Gozen (1138–ca. 1180), mother of three sons by her beloved husband, the warrior Minamoto no Yoshitomo. The story of Tokiwa Gozen is one of great tragedy. She is primarily associated, in literature and art, with how, during the Heiji Disturbance of 1160, in which her husband was betrayed and killed by his supposed ally, she fled through the snow, protecting her three young sons with her robes. She was eventually captured by that enemy, Taira no Kiyomori, a political figure of renown as the central figure in Japan’s greatest war chronicle, the Heike Monogatari. According to the ruthless rules of war, she and her sons should simply have been put to death, but Kiyomori offered to spare her children if she became his mistress. And so, while she suffered the excruciating indignity of being his mistress, her sons survived to eventually take down the ancestors of their arch enemy, Kiyomori. Among those sons was Minamoto no Yoritomo, founder of Japan’s first warrior government, the Kamakura Shogunate. Her youngest son, Minamoto no Yoshitsune, whose childhood name was Ushiwakamaru, was raised at Kuramadera temple after being torn away from his mother, and has been immortalized in legend and history as Japan’s foremost tragic hero.

Thus ends that absorbing chapter in the history of Kyoto and Japan, the Heian period.

Gretchen Mittwer

Cover:Rozanji Temple

The dyed textile artwork on the cover, designed and dyed by Keiko Kanesaki, is of the Genji Garden at Rozanji temple, located just east of the Kyoto Imperial Palace. This temple dates its history back to the year 938, and its original site is thought to be where the great grandfather of Murasaki Shikibu built a mansion, and where Murasaki Shikibu was raised, spent her brief married life, and may have written much of her lengthy and absorbing work of literary genius, The Tale of Genji. The place is mentioned in The Diary of Murasaki Shikibu, and a tile from the original structure is preserved at the temple. Imaginatively portrayed in the foreground is her writing desk and a corner of her elegant kimono sleeve.

January - February:Sennyuji Temple

Amid the imperial tombs on the hilly grounds of Sennyuji is a stone inscribed with a poem by Sei Shonagon (ca. 966–1017), author of Japan’s enduring classic, The Pillow Book. Other than the insightful impressions of the world around her which she captured in her exquisitely phrased writings, not much is known of this lady-in-waiting at the court of Empress Teishi, whose court was a center of literary activity. Sei Shonagon may have spent her last years near Sennyuji, where her beloved father had a house, and where the grave of her beloved empress is located.

March - April:Zuishin’in Temple

The imperial temple Zuishin’in, in the south of Kyoto, is associated with the poetess and unparalleled legendary beauty of the early Heian period, Ono no Komachi (ca. 825– 900). Other than what we know of her from her passionate poetry, her life remains much a mystery. It is believed, however, that she lived at this location, wherefore it has been known as the “Ono Mansion.” Zuishin’in, established in 1018, has an altar housing a statue of her, and among the other items linked to her legend is a water well where she supposedly drew water for applying her make-up.

May - June:Kifune Shrine

This Shinto shrine located deep in the northeastern mountains of Kyoto, at the source of Kyoto’s famed Kamogawa River, was patronized by the imperial family and court nobility as the source of the precious water without which life could not be sustained. It is linked in our calendar theme to the Heian period gentlewoman Izumi Shikibu (fl. ca 970–1030), considered the most gifted poet of her day. A famous episode has it that, anguishing that her husband had left her for another, she came here to pray for the return of his affections, and her prayer was answered.

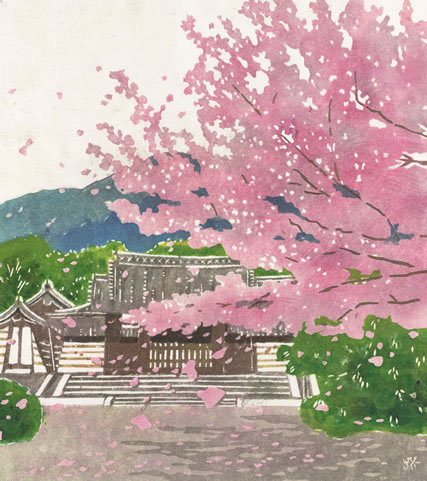

July - August:Hokongoin Temple

Were it not for our heroine Taikenmon’in (1101–1145), the once empress consort of Emperor Toba, this temple, known as “The Flower Temple” and situated in the Hanazono or “Flower Field” area of Kyoto, would not exist. Originally the villa of an aristocrat, it had fallen to ruin and was established as Hokongoin temple by Taikenmon’in, who spent her last days here as a nun. On the grounds is a cherry tree called the Taikenmon’in Sakura, reminding us of her heartrending life story, a life which burst into rosy- colored bloom, only to be quickly scattered to the winds.

September - October:Oharano Shrine

This shrine located west of Kyoto was founded when the imperial throne was moved to this area, before the founding of the Heian Capital. The influential Fujiwara clan joined in the move, and Oharano shrine is dedicated to the tutelary deity of that clan. In the Heian period, the Fujiwaras customarily came here when a Fujiwara girl was born, to pray that she could become empress or imperial consort. The Tale of Genji relates a colorful episode in 876 A.D., when Empress Takaiko and her lover, the “Radiant Genji,” were part of an imperial excursion to Oharano.

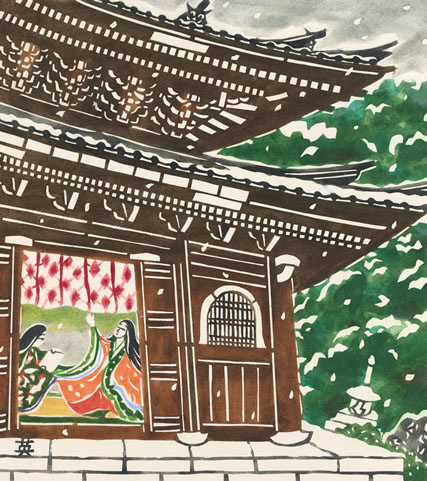

November - December:Kuramadera Temple

This page’s imaginative portrayal of Kuramadera connects us with the tragic noblewoman of the late Heian period, Tokiwa Gozen (1138–ca. 1180), and her most famous son, Minamoto no Yoshitsune. The beautiful Tokiwa Gozen sacrificed herself in exchange for the survival of her three sons. The youngest, known as Ushiwakamaru after being sent to live at the remote temple, Kuramadera, trained hard in the martial arts, and the calendar picture shows him leaping off to conquer his father and mother’s arch enemies, an event which marked the end of the Heian period.