2021 calendarClassical Poems and

Scenic Kyoto

SCROLL

Cover:Nashinoki Shrine

Decorating the calendar cover is a scene of Nashinoki Shrine when the bush clovers for which this shrine is well-known, and for which it is sometimes referred to as “The Bush Clover Palace,” are in bloom around September. This Shinto shrine is located immediately east of the Kyoto Imperial Palace, in what was formerly called the Nashinoki (Pear Tree) borough of the city. Founded in 1888, it is dedicated to the deified spirits of the court nobles Sanjo Sanetsumu and his son, Sanetomi, who were instrumental in the Meiji Restoration (1868), which ended the 264-year domination of Japan by the Tokugawa family and reestablished imperial ruling authority. The land on which the shrine stands is part of the former estate of the Sanjo family, high-ranking court nobles with lineage dating back to the late Heian Period (794–1185). On the grounds, there is a stela inscribed with a waka poem which may be translated, “In the garden a millennium ago, surely like this, the bush clovers bloomed in profusion under the shade of the trees.” It was composed by the well-known Japanese theoretical physicist, Hideki Yukawa (1907–81), the 1949 Nobel Prize laureate in Physics. Yukawa resided in a house located directly north of Nashinoki Shrine in his boyhood, and later in life he served as the first president of the shrine’s Bush Clover Society. His twentieth-century poem paints a picture for us of what could well have been a thousand-year-old garden bursting with bush clovers.

January - February:Kitano Tenmangu Shrine

The January-February page features a nighttime scene of plum blossoms and the main gate of Kitano Tenmangu Shrine, famous for its plum trees. Around February, the trees are blooming, and the delicate fragrance of their flowers wafts through air. Plum blossoms are beloved as being the first tree-flowers of the year. Having endured the harsh winter, like a miracle they come into bloom despite the continuing long nights and the persistent cold. Their flowers and scent lift the heart, for they tell us that spring has arrived. This is cleverly captured in a Heian Period waka poem by the courtier Oshikochi Mitsune (fl. 898–922) which can be rendered in English as follows: “The spring night’s darkness is in vain; the plum blossoms’ colors indeed cannot be seen, but the darkness cannot hide their scent.” Kitano Tenmangu Shrine enshrines the deified spirit of the scholar-poet Sugawara Michizane (845–903 A.D.), known as Tenman Tenjin (the Deity of the Heavens), who is revered as the divinity of learning. Michizane’s brilliance as a scholar placed him in positions of high influence at court, but alas, fierce political rivalry and jealousy soon dragged him down and he was effectively exiled to Kyushu, where he died of a broken heart, it is said. Before leaving Kyoto, he wrote a poignant poem as he gazed at the plum blossoms in his garden. It translates like this: “If an east wind blows, oh plum blossoms do send me your fragrance on it; though your master is gone, do not forget the spring.” Michizane is thus remembered for his love of the spring plum blossoms, and they are as a symbol of Kitano Tenmangu Shrine.

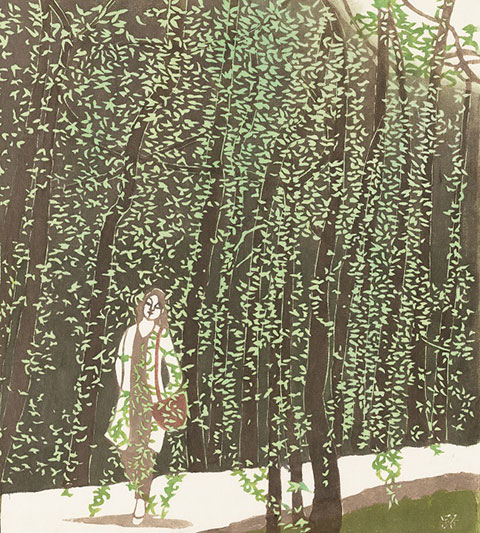

March - April:Kamogawa Riverside

In early spring, willow trees begin to reveal leaf buds on their bare branches, and seemingly in no time, the thin, dangling branches are full of bright green leaves and become lush. The inspiration for the artwork on the March-April page is the willow-lined promenade along Kyoto’s famous Kamogawa River, and a poem about spring and willows that was composed by the Heian Period courtier-poet Fujiwara Takato (949–1013). The poem, just as plausible now as it was then, can be translated, “Spring has arrived. Along the path where people come and go stepping upon the shadows of the green willows, a person stands at rest.” A stream or river lined with willow trees makes for a picturesque scene and a lovely stroll, and Kyoto is fortunate to have many of these.

May - June:Heian Shrine

On the May-June page, we have a scene of the outer worship hall at Heian Shrine. It is the grand building situated face-on from the front entrance gate to the shrine compound, and comprises the front-most building of the Daigokuden, the Great Hall of State. The fact that a Shinto shrine should have a Great Hall of State is an anomaly, reflecting the uniqueness of this particular Shinto shrine. Heian Shrine was built through the efforts of the citizens and business community of Kyoto in 1895, to celebrate the 1100th anniversary of the city’s birth in 794 A.D. as the Capital of Peace, Heian-kyo, and was designed as a reproduction, in 5/8th scale, of the official government compound of the Capital of Peace. Chinese principles of symmetry had been adopted in organizing the capital and its government, and the Daigokuden had been built in the Chinese architectural style. Fronting the Daigokuden at Heian Shrine, there is a vast graveled courtyard. On its right, if one were looking out from within the building, like the Emperor would be doing, there is an auspicious mandarin orange tree (Tachibana), which symbolizes health and longevity, and on its left is an auspicious cherry tree, a symbol of Japan. In the Kokinwakashu (a.k.a. Kokinshu; Collection of Ancient and Modern Japanese Poems; ca. 905–920), which is Japan’s earliest official, imperially commissioned anthology of waka poems, there is this lovely anonymous poem: “Smelling the scent of the mandarin orange blossoms which seem to have awaited the rice-planting month, I recall the scented sleeve of someone long ago.” Japanese is full of poetic expressions, among which are the names of the months as counted on the old lunar calendar of Japan. “The rice-planting month,” Satsuki, refers to the fifth month, which of course is called May on the standard Gregorian calendar, though it should be noted that the months on the lunar calendar do not match the timing of the Gregorian months.

July - August:Ujigawa River

For July-August, we have a fiery scene of cormorant fishing, a unique night fishing method that has a tradition of at least 1,300 years in Japan. The master fishermen who practice this technique use trained cormorants to catch river fish, such as ayu sweetfish, a summertime delicacy in Japanese cuisine. On a long wooden boat which has an iron basket filled with intensely burning firewood hanging at its prow, the master fisherman dexterously handles about a dozen cormorants on leashes. The birds swim alongside the boat and dive under the water to catch fish attracted to the light of the flame. They catch fish whole in their beaks and maneuver the fish into their expandable throat pouches. A loop around the bird’s neck prevents the bird from swallowing its catch, and the fisherman pulls the bird from the water to empty the pouch of its content of uninjured, live fish. The Ujigawa River, in the southeast of Kyoto city proper, is among the few rivers in Japan where cormorant fishing can be seen. There is an ancient poem about it, composed by Jien (1155–1225), a high priest of the Tendai sect of Buddhism, who was from the aristocratic Fujiwara family. The poem might be rendered in English like this: “I gaze with pathos at the cormorant fishing boats, their flames burning in the dark night sky at the Ujigawa.” Cormorant fishing has become a popular summer tourist attraction, where the viewers can enjoy the cool river breeze, the dramatic sight of the bright flames reflecting on the dark surface of the water, and the teamwork of the master fisherman and his cormorants, which he has carefully tended and trained over several years.

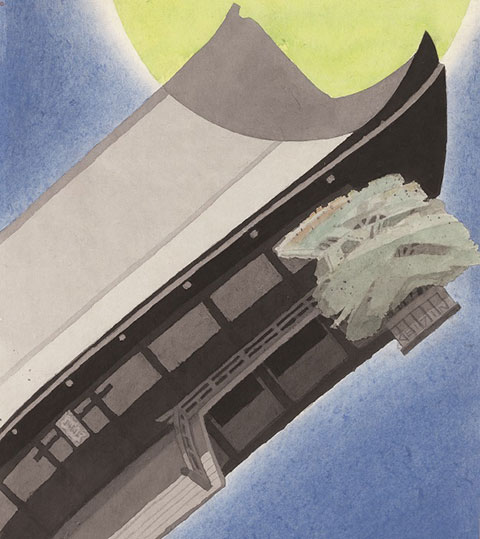

September - October:Kyoto Imperial Palace

The artwork on the September-October page is of the Shishinden building at the Kyoto Imperial Palace on the night of a full moon in autumn. Perhaps it is the fifteenth night of the eighth month on the old lunar calendar, which falls at the exact mid-point of the autumn season and is traditionally considered the night when this celestial body is brightest and most beautiful. On the standard Gregorian calendar now followed in Japan, this will fall on the 21st of September in 2021. The especially beautiful moon on this night is known as “the splendid mid-autumn moon” or, in English, the Harvest Moon. Since ancient times, the Japanese have held a special moon-viewing observance celebrating it and expressing their gratitude for a good harvest. Reaching this point in the continual passage of time and the cycle of the seasons, the daylight time from dawn to dusk starts to grow pronouncedly shorter, and life in nature gradually withers and declines. This evokes profound sentiments as to the evanescence of life. The early Heian Period courtier-poet Oe Chisato (late 9th c.) left this poem expressing his thought upon gazing at the moon in the autumn sky: “Seeing the moon, somehow I become melancholic, and I even feel as if the autumn has come only for me, though I know it is not so.” In the days when the Kyoto Imperial Palace actually was the seat of the emperor, the Shishinden palatial building which is coupled with this poem for this calendar was used for important ceremonies, such as enthronement ceremonies. The original Imperial Palace of the Heian Capital, built in the style of Chinese architecture, has long vanished. The present Kyoto Imperial Palace, with buildings in the tradition Japanese style of palatial architecture, originated as a temporary “village palace” of the Northern Court’s Emperor Kogon, when he made it his official palace in 1331.

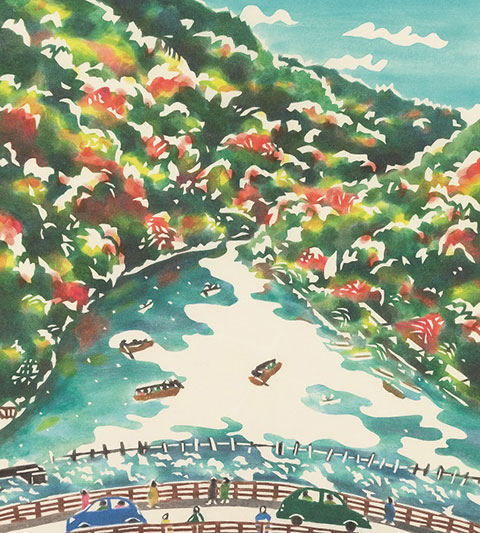

November - December:Arashiyama-Oigawa River Valley

The November-December page features a scene of the Arashiyama river valley when the maples and other deciduous trees and shrubs on the hills are radiant with their autumn colors. Flowing through the valley is the Oi River (Oigawa), which follows a winding course through a ravine by the time it reaches Arashiyama, or “Stormy Mountain,” and passes under the Togetsukyo, or “Moon-crossing Bridge.” The government minister and poet Fujiwara Suketada (d. 1021) composed a poem when he was at the Oi River viewing the autumnal scene. It might be rendered in English like this: “I could view the autumn maple leaves without concern, if only I were not at the foot of the stormy mountain.” With its lively wordplay, this poem presents a delightfully wry image. It seems that Suketada has gone to view the highly touted autumn leaves at Arashiyama, but his peaceful enjoyment of the scene is thwarted because the mountain is living up to its name this day, Stormy Mountain.