Column: Santonin, the first ascaricide made in Japan

Hisomu Ichinose, the founder of Nippon Shinyaku, had considered domestic production of exported drugs. In the later Taisho Period (1912-1926), he came up with the specific idea of producing an anthelmintic.

In those days, the Japanese had long suffered from harm from ascarids. Santonin, a specific medicine for expelling ascarids could not be produced in Japan and was imported mostly from Russia. It was a major exported medicine and was very expensive. The plant from which Santonin was produced grew only in the Kirghiz Highland in Central Asia, and Russia strictly prohibited the taking out of the seeds and seedlings of the plant under an extreme protection policy. Nippon Shinyaku strived to find a plant material for Santonin by itself and found a variety produced in Europe. They grew the plant in Japan and succeeded in extracting, from flower buds obtained, crystals of Santonin. The variety was named “Mibu-yomogi,” after the name of the place where Nippon Shinyaku had its Head Office then.

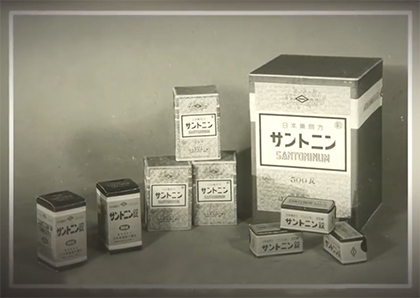

Although the plant material was secured, there were still many difficult tasks to overcome before starting domestic production, such as selecting the place for cultivating the plant, starting cultivation in broad areas, improving the breed, and developing production equipment. After spending nearly 10 years to overcome all the challenges, Nippon Shinyaku finally reached market launch of domestically produced Santonin, an anthelmintic, in 1940.

In Japan, from the middle to the end of the War, parasites, especially ascarids, were spreading due to the worsened living and hygiene environment. In some regions, 70% to 80% of the population was said to be infected by ascarids in those days. The release of Santonin, therefore, was good news for patients suffering from malnutrition due to ascaris infection.

After around 1950, however, the ascarid infection rate in Japan rapidly decreased and reached 15.5% in 1960. Besides improvements in the food situation and the hygienic environment, this decrease was largely due to the mass anthelmintic efforts both in the public and private sectors, especially the increased production of domestically made Santonin and its efficacy.

As the ascarid infection rate declined, demand for Santonin decreased naturally. With the price also sharply declining partly due to competition with other anthelmintic agents, sales of Santonin, which once accounted for around 90% of the Company’s total sales, dropped after around 1955. The ideal for a medicine is believed to be that it loses demand because its efficacy has improved the pathological condition. In this sense, the disappearance of Santonin is certainly a typical case of achieving this ideal of a medicine.